Photo:

Steven Day

June 25 2018, 1:00 p.m.

THE SECRETS ARE hidden behind

fortified walls in cities across the United States, inside towering, windowless

skyscrapers and fortress-like concrete structures that were built to withstand

earthquakes and even nuclear attack. Thousands of people pass by the buildings

each day and rarely give them a second glance, because their function is not

publicly known. They are an integral part of one of the world’s largest

telecommunications networks – and they are also linked to a controversial

National Security Agency surveillance program.

Atlanta,

Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, and

Washington, D.C. In each of these cities, The Intercept has identified an

AT&T facility containing networking equipment that transports large

quantities of internet traffic across the United States and the world. A body

of evidence – including classified NSA documents, public records, and

interviews with several former AT&T employees – indicates that the

buildings are central to an NSA spying initiative that has for years monitored

billions of emails, phone calls, and online chats passing across U.S.

territory.

The NSA

considers AT&T to be one of its most trusted partners and has lauded the

company’s “extreme willingness to help.” It is a collaboration that dates back

decades. Little known, however, is that its scope is not restricted to

AT&T’s customers. According to the NSA’s documents,

it values AT&T not only because it “has access to information that transits

the nation,” but also because it maintains unique relationships with other

phone and internet providers. The NSA exploits these relationships for

surveillance purposes, commandeering AT&T’s massive infrastructure and

using it as a platform to covertly tap into communications processed by other

companies.

Much has

previously been reported about the NSA’s surveillance programs. But few details

have been disclosed about the physical infrastructure that enables the spying.

Last year, The Intercept highlighted a

likely NSA facility in New York City’s Lower Manhattan. Now, we are revealing

for the first time a series of other buildings across the U.S. that appear to

serve a similar function, as critical parts of one of the world’s most powerful

electronic eavesdropping systems, hidden in plain sight.

“It’s

eye-opening and ominous the extent to which this is happening right here on

American soil,” said Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the Liberty and National

Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. “It puts a face on

surveillance that we could never think of before in terms of actual buildings

and actual facilities in our own cities, in our own backyards.”

There are

hundreds of AT&T-owned properties scattered across the U.S. The eight

identified by The Intercept serve a specific function, processing AT&T

customers’ data and also carrying large quantities of data from other internet

providers. They are known as “backbone” and “peering” facilities.

While

network operators would usually prefer to send data through their own networks,

often a more direct and cost-efficient path is provided by other providers’

infrastructure. If one network in a specific area of the country is overloaded

with data traffic, another operator with capacity to spare can sell or exchange

bandwidth, reducing the strain on the congested region. This exchange of traffic

is called “peering” and is an essential feature of the internet.

Because of

AT&T’s position as one of the U.S.’s leading telecommunications companies,

it has a large network that is frequently used by other providers to transport

their customers’ data. Companies that “peer” with AT&T include the American

telecommunications giants Sprint, Cogent Communications, and Level 3, as well

as foreign companies such as Sweden’s Telia, India’s Tata Communications,

Italy’s Telecom Italia, and Germany’s Deutsche Telekom.

AT&T

currently boasts 19,500 “points of presence” in 149 countries where

internet traffic is exchanged. But only eight of the company’s facilities in

the U.S. offer direct access to its “common backbone” – key data routes that

carry vast amounts of emails, internet chats, social media updates, and

internet browsing sessions. These eight locations are among the most important

in AT&T’s global network. They are also highly valued by the NSA, documents

indicate.

The data

exchange between AT&T and other networks initially takes place outside

AT&T’s control, sources said, at third-party data centers that are owned

and operated by companies such as California’s Equinix. But the data is then

routed – in whole or in part – through the eight AT&T buildings, where the

NSA taps into it. By monitoring what it calls the “peering circuits” at the

eight sites, the spy agency can collect “not only AT&T’s data, they get all

the data that’s interchanged between AT&T’s network and other companies,”

according to Mark Klein, a former AT&T technician who worked with the

company for 22 years. It is an efficient point to conduct internet

surveillance, Klein said, “because the peering links, by the nature of the

connections, are liable to carry everybody’s traffic at one point or another

during the day, or the week, or the year.”

Christopher

Augustine, a spokesperson for the NSA, said in a statement that the agency

could “neither confirm nor deny its role in alleged classified intelligence

activities.” Augustine declined to answer questions about the AT&T

facilities, but said that the NSA “conducts its foreign signals intelligence

mission under the legal authorities established by Congress and is bound by

both policy and law to protect U.S. persons’ privacy and civil liberties.”

Jim Greer,

an AT&T spokesperson, said that AT&T was “required by law to provide

information to government and law enforcement entities by complying with court

orders, subpoenas, lawful discovery requests, and other legal requirements.” He

added that the company provides “voluntary assistance to law enforcement when a

person’s life is in danger and in other immediate, emergency situations. In all

cases, we ensure that requests for assistance are valid and that we act in

compliance with the law.”

Dave

Schaeffer, CEO of Cogent Communications, told The Intercept that he had no

knowledge of the surveillance at the eight AT&T buildings, but said he

believed “the core premise that the NSA or some other agency would like to look

at traffic … at an AT&T facility.” He said he suspected that the

surveillance is likely carried out on “a limited basis,” due to technical and

cost constraints. If the NSA were trying to “ubiquitously monitor” data passing

across AT&T’s networks, Schaeffer added, he would be “extremely concerned.”

Sprint,

Telia, Tata Communications, Telecom Italia, and Deutsche Telekom did not

respond to requests for comment. CenturyLink, which owns Level 3, said it would

not discuss “matters of national security.”

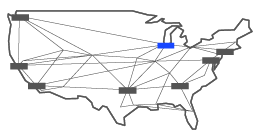

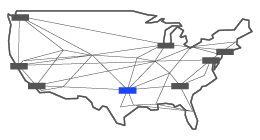

The maps

The Intercept used to identify the internet surveillance hubs.

Maps:

NSA/AT&T

THE EIGHT LOCATIONS are featured on a

top-secret NSA map, which depicts U.S. facilities that the agency relies upon

for one of its largest surveillance programs, code-named FAIRVIEW.

AT&T is the only company involved in FAIRVIEW, which was first established

in 1985, according to NSA documents, and involves tapping into international

telecommunications cables, routers, and switches.

In 2003,

the NSA launched new internet mass surveillance methods, which were pioneered

under the FAIRVIEW program. The methods were used by the agency to collect –

within a few months – some 400 billion records about people’s internet

communications and activity, the New York Times previously

reported. FAIRVIEW was also forwarding more than 1 million emails every day

to a “keyword selection system” at the NSA’s Fort Meade headquarters.

Central to

the internet spying are eight “peering link router complex” sites, which are

pinpointed on the top-secret NSA map. The locations of the sites mirror maps of

AT&T’s networks, obtained by The Intercept from public records, which show

“backbone node with peering” facilities in Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Los

Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

One of the

AT&T maps contains unique codes individually identifying the addresses of

the facilities in each of the cities.

Among the

pinpointed buildings, there is a nuclear blast-resistant, windowless facility

in New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood; in Washington, D.C., a

fortress-like, concrete structure less than half a mile south of the U.S.

Capitol; in Chicago, an earthquake-resistant skyscraper in the West Loop Gate

area; in Atlanta, a 429-foot art deco structure in the heart of the city’s

downtown district; and in Dallas, a cube-like building with narrow windows and

large vents on its exterior, located in the Old East district.

Elsewhere,

on the west coast of the U.S., there are three more facilities: in downtown Los

Angeles, a striking concrete tower near the Walt Disney Concert Hall and the

Staples Center, two blocks from the most important internet exchange in the

region; in Seattle, a 15-story building with blacked-out windows and reinforced

concrete foundations, near the city’s waterfront; and in San Francisco’s South

of Market neighborhood, a building where it was previously claimed that the NSA

was monitoring internet traffic from a secure room on the sixth floor.

The peering

sites – otherwise known in AT&T parlance as “Service Node Routing

Complexes,” or SNRCs – were developed following the internet boom in the

mid- to late 1990s. By March 2009, the NSA’s documents say it was tapping into

“peering circuits at the eight SNRCs.”

The

facilities’ purpose was to bolster AT&T’s network, improving its

reliability and enabling future growth. They were developed under the

leadership of an Iranian-American innovator and engineer named Hossein

Eslambolchi, who was formerly AT&T’s chief technology officer and president

of AT&T Labs, a division of the company that focuses on research and

development.

Eslambolchi

told The Intercept that the project to set up the facilities began after

AT&T asked him to help create “the largest internet protocol network in the

world.” He obliged and began implementing his network design by placing large

Cisco routers inside former AT&T phone switching facilities across the U.S.

When planning the project, he said he divided AT&T’s network into different

regions, “and in every quadrant I will have what I will call an SNRC.”

During his

employment with AT&T, Eslambolchi said he had to take a polygraph test, and

he obtained a government security clearance. “I was involved in very, very top,

heavy-duty projects for a few of these three-letter agencies,” he said, in an

apparent reference to U.S. intelligence agencies. “They all loved me.”

He would

not confirm or deny the exact locations of the eight peering sites identified

by The Intercept or discuss the classified work he carried out while with the

company. “You put a gun to my head,” he said, “I’m not going to tell you.”

Other

former AT&T employees, however, were more forthcoming.

A former

senior member of AT&T’s technical staff, who spoke on condition of

anonymity due to the sensitivity of the subject, confirmed with “100 percent”

certainty the locations of six of the eight peering facilities identified by

The Intercept. The source, citing direct knowledge of the facilities and their

function, verified the addresses of the buildings in Atlanta, Dallas, Los

Angeles, New York City, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

A second

former AT&T employee confirmed the locations of the remaining two sites, in

Chicago and San Francisco. “I worked with all of them,” said Philip Long, who

was employed by AT&T for more than two decades as a technician servicing

its networks. Long’s work with AT&T was carried out mostly in California,

but he said his job required him to be in contact with the company’s other

facilities across the U.S. In about 2005, Long recalled, he received orders to

move “every internet backbone circuit I had in northern California” through the

San Francisco AT&T building identified by The Intercept as one of the eight

NSA spy hubs. Long said that, at the time, he felt suspicious of the changes,

because they were unusual and unnecessary. “We thought we were routing our

circuits so that they could grab all the data,” he said. “We thought it was the

government listening.” He retired from his job with AT&T in 2014.

A third

former AT&T employee reviewed The Intercept’s research and said he believed

it accurately identified all eight of the facilities. “The site data certainly

seems correct,” said Thomas Saunders, who worked as a data networking

consultant for AT&T in New York City between 1995 and 2004. “Those nodes

aren’t going to move.”

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

AN ESTIMATED 99 PERCENT of the world’s intercontinental internet

traffic is transported through hundreds of giant fiber optic cables hidden

beneath the world’s oceans. A large portion of the data and communications that

pass across the cables is routed at one point through the U.S., partly because

of the country’s location – situated between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia

– and partly because of the pre-eminence of American internet companies, which

provide services to people globally.

The NSA

calls this predicament “home field advantage” – a kind of geographic good

fortune. “A target’s phone call, email, or chat will take the cheapest path,

not the physically most direct path,” one agency document explains.

“Your target’s communications could easily be flowing into and through the

U.S.”

Once the

internet traffic arrives on U.S. soil, it is processed by American companies.

And that is why, for the NSA, AT&T is so indispensable. The company claims

it has one of the world’s most powerful networks, the largest of its kind in

the U.S. AT&T routinely handles masses of emails, phone calls, and internet

chats. As of March 2018, some 197 petabytes of data – the equivalent of more

than 49 trillion pages of text, or 60 billion average-sized mp3 files –

traveled across its networks every business day.

The NSA

documents, which come from the trove provided to The Intercept by the

whistleblower Edward Snowden, describe AT&T as having been “aggressively

involved” in aiding the agency’s surveillance programs. One example of this

appears to have taken place at the eight facilities under a classified

initiative called SAGUARO.

As part of

SAGUARO, AT&T developed a strategy to help the NSA electronically eavesdrop

on internet data from the “peering circuits” at the eight sites, which were

said to connect to the “common backbone,” major data routes carrying internet

traffic.

The company

worked with the NSA to rank communications flowing through its networks on the

basis of intelligence value, prioritizing data depending on which country it

was derived from, according to a top-secret agency

document.

Graphic:

NSA

NSA diagrams reveal

that after it collects data from AT&T’s “access links” and “peering

partners,” it is sent to a “centralized processing facility”

code-named PINECONE, located somewhere in New Jersey. Inside the PINECONE

facility, there is a secure space in which there is both NSA-controlled and

AT&T-controlled equipment. Internet traffic passes through an AT&T

“distribution box” to two NSA systems. From there, the data is then transferred

about 200 miles southwest to its final destination: NSA headquarters at Fort

Meade in Maryland.

At the

Maryland compound, the communications collected from AT&T’s networks are

integrated into powerful systems called MAINWAY and MARINA,

which the NSA uses to analyze metadata – such as the “to” and “from” parts of

emails, and the times and dates they were sent. The communications obtained

from AT&T are also made accessible through a tool named XKEYSCORE,

which NSA employees use to search through the full contents of emails, instant

messenger chats, web-browsing histories, webcam photos, information about

downloads from online services, and Skype sessions.

Top left /

right: Mike Osborne. Bottom left: Henrik Moltke. Bottom right: Frank Heath.

THE NSA’S PRIMARY mission is to gather

foreign intelligence. The agency has broad legal powers to monitor emails,

phone calls, and other forms of correspondence as they are being transported

across the U.S., and it can compel companies such as AT&T to install

surveillance equipment within their networks.

Under a

Ronald Reagan-era presidential directive – Executive

Order 12333 – the NSA has what it calls “transit authority,” which it

says enables it to eavesdrop on “communications which originate and terminate

in foreign countries, but traverse U.S. territory.” That could include, for

example, an email sent by a person in France to a person in Mexico, which on

its way to its destination was routed through a server in California. According

to the NSA’s documents, it was using AT&T’s networks as of March 2013 to

gather some 60 million foreign-to-foreign emails every day, 1.8 billion per

month.

Without an

individualized court order, it is illegal for the NSA to spy on communications

that are wholly domestic, such as emails sent back and forth between two

Americans living in Texas. However, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the

agency began eavesdropping on Americans’ international calls and emails that

were passing between the U.S. and other countries. That practice was exposed

by the New York Times in 2005 and triggered what became known as the

“warrantless wiretapping” scandal.

Critics

argued that the surveillance of Americans’ international communications was

illegal, because the NSA had carried it out without obtaining warrants from a

judge and had instead acted on the orders of President George W. Bush. In 2008,

Congress weighed into the dispute and controversially authorized elements of

the warrantless wiretapping program by enacting Section 702 of the Foreign

Intelligence and Surveillance Act, or FISA. The new law allowed the NSA to

continue sweeping up Americans’ international communications without a warrant,

so long as it did so “incidentally” while it was targeting foreigners overseas

– for instance, if it was monitoring people in Pakistan, and they were talking

with Americans in the U.S. by phone, email, or through an internet chat

service.

Within

AT&T’s networks, there is filtering equipment designed to separate foreign

and domestic internet data before it is passed to the NSA, the agency’s

documents show. Filtering technology is often used by internet providers for

security reasons, enabling them to keep tabs on problems with their networks,

block out spam, or monitor hacking attacks. But the same tools can be used for

government surveillance.

“You can

essentially trick the routers into redirecting a small subset of traffic you

really care about, which you can monitor in more detail,” said Jennifer

Rexford, a computer scientist who worked for AT&T Labs between 1996 and

2005.

According

to the NSA’s documents,

it programs its surveillance systems to focus on particular IP addresses – a

set of numbers that identify a computer – associated with foreign countries. A

classified 2012 memo describes the agency’s efforts to use IP addresses to home

in on internet data passing between the U.S. and particular “regions of

interest,” including Iran, Afghanistan, Israel, Nigeria, Pakistan, Yemen,

Sudan, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. But this process is not an exact science, as

people can use privacy or anonymity tools to change or spoof their IP

addresses. A person in Israel could use privacy software to masquerade as if

they were accessing the internet in the U.S. Likewise, an internet user in the

U.S. could make it appear as if they were online in Israel. It is unclear how

effective the NSA’s systems are at detecting such anomalies.

In October

2011, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which approves the

surveillance operations carried out under Section 702 of FISA, found that there

were “technological limitations” with the agency’s internet eavesdropping

equipment. It was “generally incapable of distinguishing” between some kinds of

data, the court stated. As a consequence, Judge John D. Bates ruled,

the NSA had been intercepting the communications of “non-target United States

persons and persons in the United States,” violating Fourth Amendment

protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. The ruling, which was

declassified in August 2013, concluded that the agency had acquired some 13

million “internet transactions” during one six-month period, and had unlawfully

gathered “tens of thousands of wholly domestic communications” each year.

The root of

the issue was that the NSA’s technology was not only targeting communications

sent to and from specific surveillance targets. Instead, the agency was

sweeping up people’s emails if they had merely mentioned particular

information about surveillance targets.

A top-secret

NSA memo about the court’s ruling, which has not been disclosed

before, explained that the agency was collecting people’s messages en masse if

a single one were found to contain a “selector” – like an email address or

phone number – that featured on a target list.

“One

example of this is when a user of a webmail service accesses her inbox; if the

inbox contains one email message that contains an NSA tasked selector, NSA will

acquire a copy of the entire inbox, not just the individual email message that

contains the tasked selector,” the memo stated.

The court’s

ruling left the agency with two options: shut down the spying based on mentions

of targets completely, or ensure that protections were put in place to stop the

unlawfully collected communications from being reviewed. The NSA chose the

latter option, and created a “cautionary banner” that warned its analysts not

to read particular messages unless they could confirm that they had been

lawfully obtained.

But the

cautionary banner did not solve the problem. The NSA’s analysts continued to

access the same data repositories to search, unlawfully, for information on

Americans. In April 2017, the agency publicly

acknowledged these violations, which it described as “inadvertent

compliance incidents.” It said that it would no longer use surveillance

programs authorized under Section 702 of FISA to harvest messages that

mentioned its targets, citing “technological constraints, United States person

privacy interests, and certain difficulties in implementation.”

The

messages that the NSA had unlawfully collected were swept up using a method of

surveillance known as “upstream,” which the agency still deploys for other

surveillance programs authorized under both Section 702 of FISA and Executive

Order 12333. The upstream method involves tapping into communications as they

are passing across internet networks – precisely the kind of electronic

eavesdropping that appears to have taken place at the eight locations

identified by The Intercept.

Photo:

Frank Heath

Atlanta 51 Peachtree

Center Avenue

The

AT&T building in Atlanta was originally constructed in the 1920s as the

main telephone exchange for the city’s downtown area. The art deco structure,

made of limestone, was designed to be the largest in the city at the time at 25

stories tall. However, due to the Great Depression, plans were scaled back and

at first, it only had six stories. Between 1947 and 1963, the building was

upgraded to host 14 stories, and a large brown microwave tower – visible for

miles – was also added. A profile of the building on the History

Atlanta website notes that it contains “operations, phone exchanges

and other communications equipment for AT&T.”

Photo:

Frank Heath

NSA and

AT&T maps point to the Atlanta facility as being one of eight “peering”

hubs that process internet traffic as part of the NSA surveillance program

code-named FAIRVIEW. One former AT&T employee – who spoke on condition

of anonymity – confirmed that the site was one of eight primary AT&T “Service

Node Routing Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA documents explicitly

describe tapping into flows of data at all eight of these sites.

Information

provided by a second former AT&T employee adds to the evidence linking the

Atlanta building to NSA surveillance. Mark Klein, a former AT&T technician,

alleged in 2006 that the company had allowed the NSA to install surveillance

equipment in some of its network hubs. An AT&T facility in Atlanta was one

of the spy sites, according to documents Klein presented in a court case over

the alleged spying. The Atlanta facility was equipped with “splitter”

equipment, which was used to make copies of internet traffic as AT&T’s

networks processed it. The copied data would then be diverted to “SG3” equipment

– a reference to “Study Group 3” – which was a code name AT&T used for

activities related to NSA surveillance, according to evidence in the Klein

case.

The Atlanta

facility is likely of strategic importance for the NSA. The site is the closest

major AT&T internet routing center to Miami, according to the NSA and

AT&T maps. From undersea cables that come aground at Miami, huge flows of

data pass between the U.S. and South America. It is probable that much of that

data is routed through the Atlanta facility as it is being sent to and from the

U.S. In recent years, the NSA has extensively targeted several Latin American

countries – such as Mexico, Brazil, and Venezuela – for surveillance.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

Chicago 10 South Canal

Street

Like many

other major telecommunications hubs built during the late 1960s and early

1970s, the Chicago AT&T building was designed amid the Cold War to

withstand a nuclear attack. The 538-foot skyscraper, located in the West Loop

Gate area of the city, was completed in 1971. There are windows at both the top

and bottom of the vast concrete structure, but 18 of its 28 floors are

windowless.

According

to the Chicago Sun-Times, the facility handles much of the city’s phone and

internet traffic and is equipped with banks of routers, servers, and switching

systems. “This building touches every single resident of the city,” Jim Wilson,

an AT&T area manager, told the

newspaper in 2016.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

One of the

building’s architects, John Augur Holabird, said in

a 1998 interview that it housed “a big switchboard.” He added: “In case the

atomic bomb hits Milwaukee, you’ll be happy to know your telephone line will

still go through even though the rest of us are wiped out. And that’s what that

building was for.”

10 South

Canal Street originally contained a million-gallon oil tank, turbine

generators, and a water well, so that it could continue to function for more

than two weeks without electricity or water from the city, according to

Illinois broadcaster WBEZ. The building is “anchored in bedrock, which helps

support the weight of the equipment inside, and gives it extra resistance to

bomb blasts or earthquakes,” WBEZ reported.

Today, the

facility contains six large V-16 yellow Caterpillar generators that can provide

backup electricity in the event of a power failure, according to

the Chicago Sun Times. Inside the skyscraper, AT&T stores some 200,000

gallons of diesel fuel, enough to run the generators for 40 days.

NSA and

AT&T maps point to the Chicago facility as being one of the “peering” hubs,

which process internet traffic as part of the NSA surveillance program

code-named FAIRVIEW. Philip Long, who was employed by AT&T for more

than two decades as a technician servicing its networks, confirmed that the

Chicago site was one of eight primary AT&T “Service Node Routing

Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA documents explicitly describe

tapping into flows of data at all eight of these sites.

Photo: Mike

Osborne

Dallas 4211 Bryan Street

This

AT&T building is a fortified, cube-like structure, located in the Old East

area of Dallas, not far from Baylor University Medical Center. Built in 1961,

it is a light yellow-brown color with a granite foundation. Large vents are

visible on the exterior of the building, as are several narrow windows, many of

which appear to have been blacked out or covered in a reflective privacy glass.

The 4211

Bryan Street facility is located next to other AT&T-owned buildings,

including a towering telephone routing complex that was first built in 1904.

A piece about

the telephone hub in the Dallas Observer described it as “an imposing, creepy

building” that is “known in some circles as The Great Wall of Beige.”

Photo: Mike

Osborne

According

to the Central Office website,

which profiles telecommunications buildings across the U.S., the Dallas

telephone hub is “the main regional tandem and AT&T for long distance and

toll services in the Dallas Texas region.” Today, the building also has “major

fiber connections to Plano, Irving, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, Ft. Worth, Abilene,

Houston and Austin,” the website adds.

NSA and

AT&T maps point to the 4211 Bryan Street facility as being one of the

“peering” hubs, which process internet traffic as part of the NSA surveillance

program code-named FAIRVIEW. A former AT&T employee confirmed that the

site was one of eight primary AT&T “Service Node Routing

Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA documents explicitly describe tapping

into flows of data at all eight of these sites.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

Los Angeles 420 South

Grand Avenue

At the time

of its construction in 1961, the AT&T building known as the Madison Complex

was the tallest building in downtown Los Angeles. It has since been dwarfed by

a number of corporate office skyscrapers in the surrounding Financial District.

Located

between Chinatown and the Staples Center, the fortress-like structure is one of

the largest telephone central offices in the U.S. “The theoretical number of

telephone lines that can be served from this office are 1.3 million and this

office also serves as a foreign exchange carrier to neighboring area codes,”

according to the Central

Office, a website that profiles U.S. telecommunications hubs.

“Untitled,

or Bell Communications Around the Globe”. Mural by Anthony Heinsbergen (1961)

on the West side of 420 South Grand Ave, La.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

The 448-foot,

17-story building is beige, rectangular, and mostly windowless. On its roof,

there is a large microwave tower, which was originally used to transmit phone

calls across a network of antennae. The tower’s technology became obsolete in

the early 1990s, and it ceased to operate. It remains in place today as a sort

of monument to outdated methods of communication and stands in contrast to the

more modern buildings in the vicinity, many of them owned by banks.

The Madison

Complex is located just two blocks from One Wilshire, which houses what is

reportedly the most important internet exchange on the U.S. west coast.

“Billions of phone calls, emails and internet pages pass through One Wilshire

every week,” the Los Angeles Times reported in

2013, “because it is the primary terminus for major fiber-optic cable routes

between Asia and North America.”

Due to the

close proximity of the Madison Complex and One Wilshire, and their shared role

as telecommunications hubs, it is likely that the buildings process some of the

same data as it is being routed across U.S. networks.

NSA and

AT&T maps point to the Madison Complex facility as being one of the

“peering” hubs, which process internet traffic as part of the NSA surveillance

program code-named FAIRVIEW. A former AT&T employee confirmed that the

site was one of eight primary AT&T “Service Node Routing

Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA documents explicitly describe

tapping into flows of data at all eight of these sites.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

New York City 811 10th

Avenue

It was

built in 1964 as New York City’s first major telecommunications fortress. The

striking concrete and granite AT&T building – located in the Hell’s Kitchen

area about a 15-minute walk from Central Park – is 134 meters tall, with 21

floors, each one of them windowless and built to resist a nuclear blast.

A New York

Times article published

in 1975 noted that 811 10th Avenue was “the first of several windowless

equipment buildings to be constructed” in the city, and added that its design

initially “caused considerable controversy.”

Aerial shot

of 811 10th street, NYC, ca. 1965.

Photo:

courtesy of Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

According

to AT&T records,

the building is a “hardened telco data center” and was upgraded in 2000 to

become an internet data center. Thomas Saunders, a former AT&T engineer,

told The Intercept that, in the 1970s, the building was considered to be “the

biggest hub for transmission [of communications] in the country.” Saunders also

claimed that, had Bush been in Manhattan during the 9/11 attacks, the Secret

Service would have taken him to safety inside the AT&T facility. “It’s the

strongest building in town,” he said.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

NSA and

AT&T maps indicate that the 10th Avenue facility is one of eight “peering”

hubs that process internet traffic as part of the NSA surveillance program

code-named FAIRVIEW. Two former AT&T employees confirmed that the site

was one of eight primary AT&T “Service Node Routing

Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA documents explicitly describe

tapping into flows of data at all eight of these sites.

The design

of the building bears some resemblance to another windowless building in New

York City – AT&T’s towering skyscraper at 33 Thomas Street in lower

Manhattan. As The Intercept reported in

2016, 33 Thomas Street is a major hub for routing international phone calls and

appears to contain a secure NSA surveillance room – code-named TITANPOINTE –

that has been used to tap into faxes and phone calls.

NSA and

AT&T documents indicate that 10th Avenue building serves as the NSA’s

internet equivalent of 33 Thomas Street. While the NSA’s surveillance at 33

Thomas Street mainly targets phone calls that pass through the building’s

international switching points, at the 10th Avenue site the agency appears to primarily

collect emails, online chats, and data from internet browsing sessions.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

San Francisco 611 Folsom

Street

This San

Francisco AT&T building has been described as the city’s telecommunications

“nerve center.” It is about 256 feet tall, has nine floors, and its exterior is

covered in silver-colored panels; there are a series of vents that can be seen

at street level, but there are few windows.

NSA and

AT&T maps obtained by The Intercept indicate that 611 Folsom Street is one

of the eight “peering” hubs in the U.S. that process internet traffic as part

of the NSA surveillance program code-named FAIRVIEW. Philip Long, who was

employed by AT&T for more than two decades as a technician servicing its

networks, confirmed that the San Francisco site is one of eight primary

AT&T “Service Node Routing Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA

documents explicitly describe tapping into flows of data at all eight of these

sites.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

Long

recalled that, in the early 2000s, he “moved every internet backbone circuit I

had in northern California” through the Folsom Street office. At the time, he

said, he and his colleagues found it strange that they were asked to suddenly

reroute all of the traffic, because “there was nothing wrong with the services,

no facility problems.”

“We were

getting orders to move backbones … and it just grabbed me,” said Long. “We

thought it was government stuff and that they were being intrusive. We thought

we were routing our circuits so that they could grab all the data.”

It is not

the first time the building has been implicated in revelations about electronic

eavesdropping. In 2006, an AT&T technician named Mark Klein alleged in a

sworn court declaration that the NSA was tapping into internet traffic from a

secure room on the sixth floor of the facility.

Klein, who

worked at 611 Folsom Street between October 2003 and May 2004, stated that

employees from the agency had visited the building and recruited one of

AT&T’s management level technicians to carry out a “special job.” The job

involved installing a “splitter cabinet” that copied internet data as it was

flowing into the building, before diverting it into the secure room.

The room at

AT&T’s Folsom St. facility that allegedly contained NSA surveillance

equipment.

Photo: Mark

Klein

He said

equipment in the secure room included a “semantic traffic analyzer” – a tool

that can be used to search large quantities of data for particular words or

phrases contained in emails or online chats. Notably, Klein discovered that the

NSA appeared to be specifically targeting internet “peering links,” which is

corroborated by the NSA and AT&T documents obtained by The Intercept.

“By cutting

into the peering links, they get not only AT&T’s data, they get all the data

that’s interchanged between AT&T’s network and other companies,” Klein told

The Intercept in a recent interview.

According

to documents provided by Klein, AT&T’s network at Folsom Street “peered”

with other companies like Sprint, Cable & Wireless, and Qwest. It was also

linked, he said, to an internet exchange named MAE West, a major data hub in

San Jose, California, where other companies connect their networks together.

Sprint did

not respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson for Cable & Wireless

said the company only discloses data “when legally required to do so as a

result of a valid warrant or other legal process.” In 2011, CenturyLink

acquired Qwest as part of a $12.2 billion merger deal. A CenturyLink

spokesperson said he could not discuss “matters of national security.”

Photo:

Jovelle Tamayo for The Intercept

Seattle 1122 3rd Avenue

The Seattle

facility is located in the city’s downtown area, not far from the waterfront.

The gray building is 15 stories tall, with a dozen rows of narrow, blacked-out

windows and vents that rise to its peak. According to public records, it was first

constructed in 1955 and has reinforced concrete foundations and exterior walls

that are supported by a steel frame.

Historically,

the facility was an important communications switching point in the northwest

of the U.S., routing calls between places like Bellingham, Spokane, Yakima, and

north to Canada and Alaska. Today, the building appears to be primarily ownedby

the Qwest Corporation – a subsidiary of CenturyLink – but AT&T has a

presence within it. AT&T’s logo is emblazoned on a plaque outside the building’s

entrance.

Twenty-five

miles north of Seattle, there is a major intercontinental undersea cable called

Pacific Crossing-1, which routes communications between the U.S. and Japan; it

is possible that the Seattle building processes some of these communications

and others that pass between the U.S. west coast and Asia.

Photo:

Jovelle Tamayo for The Intercept

NSA and

AT&T maps point to the Seattle facility as being of eight “peering” hubs

that process internet traffic as part of the NSA surveillance program

code-named FAIRVIEW. A former AT&T employee confirmed that the site

was one of eight primary AT&T “Service Node Routing

Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA documents explicitly describe

tapping into flows of data at all eight of these sites.

Photo:

Henrik Moltke

Washington, D.C. 30 E

Street Southwest

The

building is a large, concrete, rectangular-shaped facility with few windows,

located less than a mile south of the U.S. Capitol. Property tax records show

that Verizon owns the majority of the property (worth $26 million), while

AT&T owns a smaller part (worth $8.8 million). Plans of the building’s

internal layout show that AT&T has space on the fourth, fifth, and sixth

floors.

Central

Office Buildings, a website that

profiles telecommunications hubs in North America, describes the 30 E Street

South West facility as “the granddaddy HQ of Verizon landline in Washington,

DC.” It adds that the building contains a “a slew of switches of various

types,” including AT&T equipment for routing long distance phone calls

across networks.

Photo: Mike

Osborne

Capitol

Police has an office located opposite the telecommunications hub, and a large

number of police vehicles are usually located around the site. When The

Intercept visited the facility to take photographs earlier this year, within a

few minutes, several armed police officers arrived on the scene with dogs. They

questioned our reporter, searched his car, and said that the building was considered

critical infrastructure.

NSA and

AT&T maps point to the Washington, D.C. facility as being one of eight

“peering” hubs that process internet traffic as part of the NSA surveillance

program code-named FAIRVIEW. A former AT&T employee confirmed that the

site was one of eight primary AT&T “Service Node Routing

Complexes,” or SNRCs, in the U.S. NSA documents explicitly describe

tapping into flows of data at all eight of these sites.

Documents

Documents

published with this article:

- FAA702

comms memo

- FAIRVIEW

brief overview

- FAIRVIEW

overview with notes

- SSO

dictionary relevant entries

- SSO

news relevant entries

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.