July 18, 2018 • 96 Comments

Amidst the backdrop of increased

U.S.-Russian tensions and even talk of war, long forgotten is the time the U.S.

actually invaded, explains Jeff Klein.

By Jeff Klein

Special to Consortium News

Special to Consortium News

Amid the bi-partisan mania over the

Trump-Putin Summit in Helsinki, fevered, anti-Russian rhetoric in the United

States makes conceivable what until recently seemed inconcievable: that

dangerous tensions between Russia and the U.S. could lead to military conflict.

It has happened before.

In September 1959, during a brief

thaw in the Cold War, Nikita Khrushchev made his famous visit to the United

States. In Los Angeles, the Soviet leader was invited to a luncheon

at Twentieth Century-Fox Studios in Hollywood and during a long

and rambling exchange he had this to say:

“Your armed intervention in Russia

was the most unpleasant thing that ever occurred in the relations between

our two countries, for we had never waged war against America until then;

our troops have never set foot on American soil, while your troops have

set foot on Soviet soil.”

These remarks by Khrushchev were

little noted in the U.S. press at the time – especially compared to his widely-reported complaint

about not being allowed to visit Disneyland. But even if Americans read

about Khrushchev’s comments it is likely that few of them would have had any

idea what the Soviet Premier was talking about.

But Soviet – and now Russian — memory

is much more persistent. The wounds of foreign invasions, from

Napoleon to the Nazis, were still fresh in Russian public consciousness in 1959

— and even in Russia today — in a way most Americans could not imagine.

Among other things, that is why the Russians reacted with so much outrage to

the expansion of NATO to its borders in the 1990’s, despite U.S. promises not

to do so during the negotiations for the unification of Germany.

The U.S. invasion Khrushchev referred

to took place a century ago, after the October Revolution and during the civil

war that followed between Bolshevik and anti-Bolshevik forces, the Red Army

against White Russians. While the Germans and Austrians were occupying

parts of Western and Southern Russia, the Allies launched their own armed

interventions in the Russian North and the Far East in 1918.

The Allied nations, including

Britain, France, Italy, Japan and the U.S., cited various justifications for

sending their troops into Russia: to “rescue” the Czech Legion that had been

recruited to fight against the Central Powers; to protect allied military

stores and keep them out of the hands of the Germans; to preserve

communications via the Trans-Siberian Railway; and possibly to re-open an

Eastern Front in the war. But the real goal – rarely admitted publicly at

first—was to reverse the events of October and install a more “acceptable” Russian

government. As Winston Churchill later put it, the aim was to “strangle the

Bolshevik infant in its cradle.”

In addition to Siberia, the U.S.

joined British and French troops to invade at Archangel, in the north of Russia, on

September 4, 1918.00

In July 1918, U.S. President

Woodrow Wilson had personally typed the “Aide Memoire” on American military action in Russia that was

hand-delivered by the Secretary of War at the beginning of August to General

William Graves, the designated commander of the U.S. troops en route to

Siberia. Wilson’s document was curiously ambivalent and contradictory. It

began by asserting that foreign interference in Russia’s internal affairs was

“impermissible,” and eventually concluded that the dispatch of U.S. troops to

Siberia was not to be considered a “military intervention.”

The Non-Intervention

Intervention

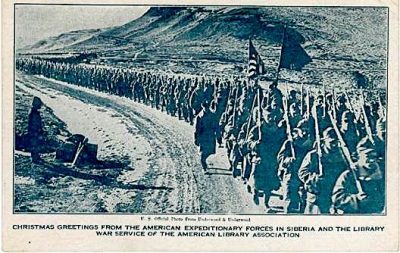

But the American intervention began

when U.S. soldiers disembarked at Vladivostok on August 16, 1918. These

were the 27th and 31st infantry regiments, regular army units that had been

involved in pacification of U.S.-occupied Philippines. Eventually there

were to be about 8,000 U.S. troops in Siberia.

Judging from his memoires, General

Graves was puzzled by how different things looked on the ground in Siberia than

his vague instructions seemed to suggest. For one thing, the Czechs

hardly needed rescuing. By the Summer of 1918 they had easily taken

control of Vladivostok and a thousand miles of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

For the next year and a half, General

Graves, by all appearances an honest and non-political professional soldier,

struggled to understand and carry out his mandate in Siberia. He seems to

have driven the U.S. State Department and his fellow allied commanders to

distraction by clinging stubbornly to a literal interpretation of

Wilson’s Aide Memoire as mandating strict non-intervention in Russian

affairs. The general seemed incapable of noticing the broad “wink” with which

everyone else understood these instructions.

Graves strove to maintain

“neutrality” among the various Russian factions battling for control of Siberia

and to focus on his mission to guard the railroad and protect Allied military

supplies. But he was also indiscrete enough to report “White” atrocities

as well as “Red” ones, to express his distaste for the various Japanese-supported

warlords in Eastern Siberia and, later, to have a skeptical (and correct)

assessment of the low popular support, incompetence and poor prospects of the

anti-Bolshevik forces.

For his troubles, it was hinted,

absurdly, that the General may have been a Bolshevik sympathizer, a charge that

in part motivated the publication of his memoirs.

In the face of hectoring by State

Department officials and other Allied commanders to be more active in support

of the “right” people in Russia, Graves repeatedly inquired of his superiors in

Washington whether his original instructions of political non-intervention were

to be modified. No one, of course, was willing to put any different policy in

writing and the general struggled to maintain his “neutrality.”

By the Spring and Summer of 1919,

however, the U.S. had joined the other Allies in providing overt military

support to “Supreme Leader,” Admiral Alexander Kolchak’s White regime, based in

the Western Siberian city of Omsk. At first this was carried out

discretely through the Red Cross, but later it took the form of direct

shipments of military supplies, including boxcars of rifles whose safe delivery

Graves was directed to oversee.

Domestic

Intervention

But the prospects for a victory by

Kolchak soon faded and the Whites in Siberia revealed themselves to be a lost

cause. The decision to remove the US troops was made late in 1919 and

General Graves, with the last of his staff, departed from Vladivostok on 1

April 1920.

In all, 174 American soldiers

were killed during the invasion of Russia. (The Soviet Union

was formed on Dec. 28, 1922.)

Interestingly, pressure to withdraw

the U.S. troops from Siberia came from fed-up soldiers and home-front opinion

opposing the continued deployment of military units abroad long after the

conclusion of the war in Europe. It is notable that during a Congressional

debate on the Russian intervention one Senator read excerpts from the letters

of American soldiers to support the case for bringing them home.

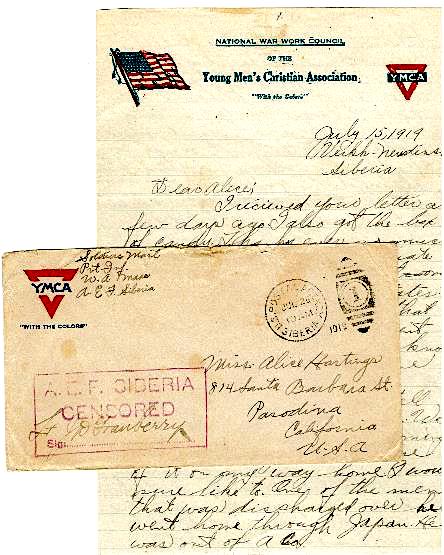

Then, as in later U.S. foreign

interventions, the soldiers had a low opinion of the people they were supposed

to be liberating. One of them wrote home on July 28, 1919 from his base

in Verkhne-Udinsk, now Ulan Ude, on the southern shore of Lake Baikal:

Letter home for U.S. soldier during

invasion of Russia

“Life in Siberia may sound exciting

but it isn’t. It’s all right for a few months but I’m ready to go home

now. . . You want to know how I like the people? Well I’ll tell

you, one couldn’t hardly call them people but they are some kind of

animal. They are the most ignorant things I ever saw. Oh, I can get

a word of their lingo if they aren’t sore when they talk. They sure do rattle

off their lingo when they get sore. These people have only one ambition

and that is to drink more vodka than the next person.”

Outside of the State Department and

some elite opinion, U.S. intervention had never been very popular.

By now it was widely understood, as one historian noted, that there may have

been “many reasons why the doughboys came to Russia, but there was only one

reason why they stayed: to intervene in a civil war to see who would govern the

country.”

After 1920, the memory of “America’s

Siberian Adventure,” as General Graves termed it, soon faded into

obscurity. The American public is notorious for its historic amnesia,

even as similar military adventures were repeated again and again over the

years since then.

It seems that we may need to be

reminded every generation or so of the perils of foreign military intervention

and the simple truth asserted by General Graves:

“. . .there isn’t a nation on earth

that would not resent foreigners sending troops into their country, for the purpose

of putting this or that faction in charge. The result is not only an

injury to the prestige of the foreigner intervening, but is a great handicap to

the faction the foreigner is trying to assist.”

General Graves was writing about

Siberia in 1918, but it could just as well have been Vietnam in the 1960s or

Afghanistan and Syria now. Or a warning today about 30,000 NATO troops on

Russia’s borders.

Jeff Klein is a

retired local trade union president who writes frequently about international

affairs and especially the Middle East. The postcard and soldier’s letter

are in his personal collection.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.