Trump infuriated and insulted South Koreans when he said “they do nothing without our approval.”

By Tim Shorrock

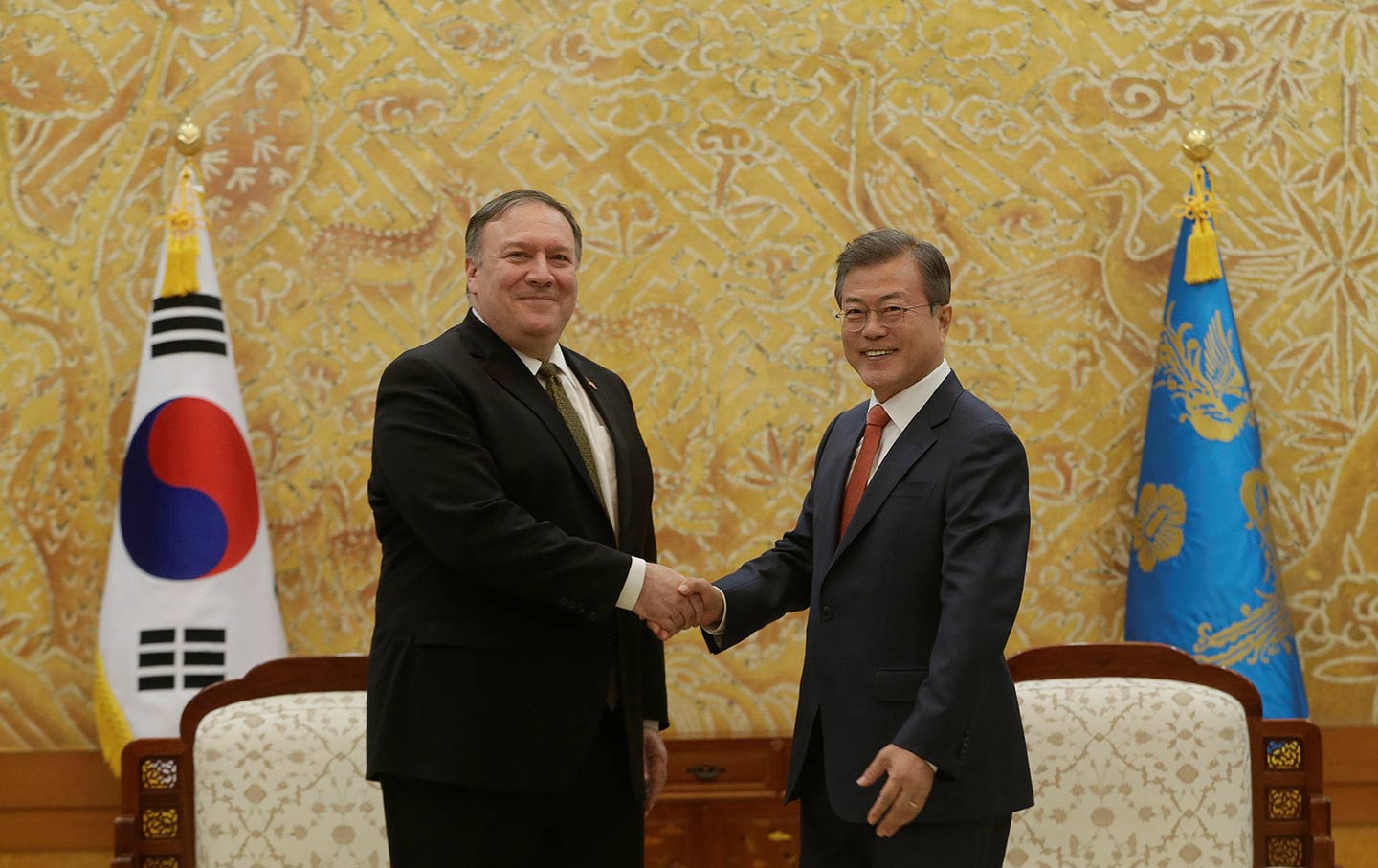

South Korean President Moon Jae-in shakes hands with US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo during a meeting in Seoul, South Korea, on October 7, 2018. (Pool via Reuters / Ahn Young-joon)

Ready To Fight Back?

Sign up for Take Action Now and get three actions in your inbox every week.

You will receive occasional promotional offers for programs that support The Nation’s journalism. You can read our Privacy Policy here.

As the two Koreas continue to move their peace process forward in the wake of their highly successful September summit in Pyongyang, the Trump administration, along with military-industrial think tanks and journalists who influence US policy, have shifted their collective indignation away from North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and toward South Korean President Moon Jae-in.

A year after threatening Kim with a “bloody nose” strike unless he stopped his nuclear buildup, the Trump administration and its allies are now going after Moon’s economic engagement with North Korea as a chief impediment to Pyongyang’s pledge to denuclearize. Moon, in their view, has weakened Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign of sanctions and military threats by moving too quickly on inter-Korean reconciliation and ignoring US demands that sanctions be lifted only after the North’s nuclear disarmament.

In contrast, the United States has stood firm. “I haven’t eased the sanctions,” President Trump told Lesley Stahl on 60 Minutes this past Sunday in comments that were overshadowed by his defense of his professed “love” for Kim Jong-un. “I haven’t done anything.” A few days earlier, Trump sent shock waves through South Korea when he was asked about reports that Moon’s government was considering the idea of terminating the sanctions and trade embargo that South Korea itself had imposed on the North in 2010.

Trump said South Korea wouldn’t lift sanctions on Pyongyang without American approval, and then repeated himself: “They do nothing without our approval.” His arrogant assumptions were too much for the JoongAng Daily, a conservative paper that generally supports US policy. “[Trump’s] choice of the word—approval—could sound very offensive as it suggests the United States denies us our sovereignty,” its editorialist wrote. The center-right Korea Times added that Trump’s statement “is seen as infringing on the national sovereignty of South Korea.”

In fact, the Moon government has been generally supportive of US and UN sanctions and has consulted with the Trump administration about lifting them in specific instances. At the same time, President Moon is seeking support for sanctions relief as US and South Korean negotiations with Pyongyang move forward. “I believe the international community needs to provide assurances that North Korea has made the right choice to denuclearize and encourage North Korea to speed up the process,” he said this week in Paris during a visit with French President Emmanuel Macron. Moon is on a nine-day tour of European capitals that was followed up on Thursday when he met with the pope at the Vatican and extended to him an invitation from Kim Jong-un to visit Pyongyang.

The US ambassador to South Korea, Harry Harris, underscored US impatience when he warned in Seoul that the US and South Korean governments must speak with one voice. “We are, of course, cognizant of the priority that President Moon Jae-in and his administration have placed on improving South-North relations,” he told a conference on Tuesday co-sponsored by the US-government-run Wilson Center. “I believe this inter-Korean dialogue must remain linked to denuclearization, and South Korea synchronized with the United States.”

In what seemed like a tit-for-tat response, South Korea’s ambassador to Washington, Cho Yoon-je, responded on Wednesday to the US concerns that Seoul is “moving too fast” on implementing its agreements with the North.

“When inter-Korean relations are moving a little faster than North Korea–US dialogue, that gives South Korea the leverage to act as a facilitator and enables it to break through deadlocks between North Korea and the US,” Cho said in a speech to South Korea’s Sejong Institute and the US Council on Foreign Relations. While agreeing that sanctions “must be implemented faithfully,” he argued that the “momentum on one side can drive the process on the other and create a virtuous cycle.” Cho pointed to the three summits between Moon and Kim as evidence, saying that they “breathed new life into North Korea–US dialogue.”

The turning point for the Trump administration’s relations with Seoul may have come on September 14, when the two Koreas opened a liaison office just north of the DMZ. They did this against the public recommendation of the State Department, which had initially warned that South Korea’s supply of electricity, water, and other supplies to the Gaesong Industrial Complex would violate US and UN sanctions. Since the virtual embassies opened, representatives from the two Koreas have had more than 60 face-to-face meetings, and the office has become a clearinghouse for over a dozen bilateral projects launched during the summit.

The Korean snub of the State Department may have triggered another flare-up in early October, when the two Koreas began removing landmines along the DMZ as part of the bilateral military agreement signed during the Pyongyang summit to prevent an accident from spiraling into another war. Their announcement of the pact greatly displeased Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. According to Korean press reports, he “furiously harangued” Moon’s top diplomat, Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha, in a blistering phone call that shocked many Koreans when its contents were made publicin a parliamentary hearing.

Pompeo’s impatience was reignited this past Monday, following a weekend agreement by the two Koreas to hold a groundbreaking ceremony in late November or December for a massive binational project to link roads and railroads severed during the Korean War. Asked to comment, a State Department official tartly observed that sanctions must be enforced until the North denuclearizes. “We expect all member states to fully implement U.N. sanctions [and] take their responsibilities seriously to help end the [North’s] illegal nuclear and missile programs,” the diplomat told Yonhap News.

RELATED ARTICLE

00

Tim Shorrok

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.