Norman Rockwell and the Rediscovery of America’s Moral Compass

A great poet once said that you can judge a nation by how it honors (or fails to honor) its artists. In many ways, the soul of a nation is entirely shaped by the artists which that society has produced. This makes perfectly good sense, as an artist is able to portray the better ideals which that society yearns to become and can convey concepts on a nearly subconscious level that may either uplift our self conception to the divine or inversely inflame our basest passions. An artist can also awaken truthful moral lessons and temper raw emotions of a people which mere lecturing/moralising could never accomplish.

In America, an artist arose in the 20th century whose passion, moral integrity and technical genius shaped and ennobled the hearts and minds of generations, and while this painter is loved in America, his works are often shrugged off as naive and sentimental devotions to a happier world that neither ever was nor could ever be. It is in the hopes of lifting this ignorant veil that I would like to offer this holiday gift presenting the life and work of Norman Rockwell (1894-1978).

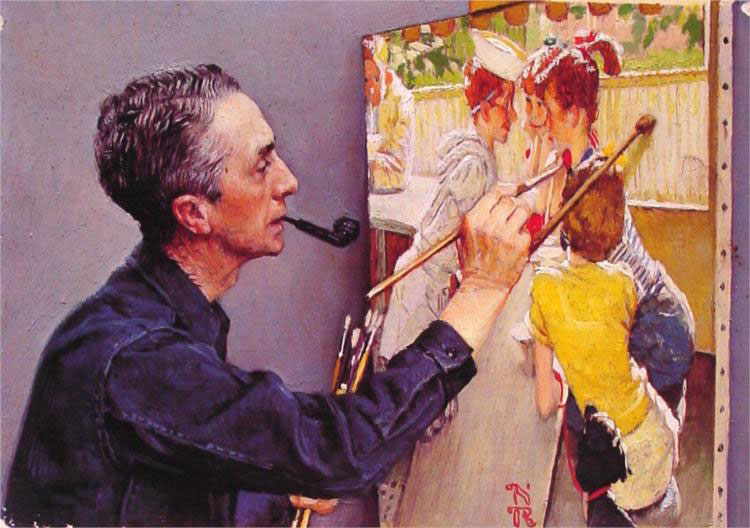

Born in New York in 1894, Norman Rockwell was inspired by the contemporary illustrations of Joseph Leyendecker and Howard Chandler Christie and especially the Dutch school of Vermeer and Rembrandt. After graduating from the National Academy of Design and Art Students’ League, Rockwell began illustrating children’s’ books and magazine covers for Boy Scouts of America. From an early age, Rockwell aspired to revive the renaissance tradition of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Raphael and DaVinci whose reproductions were always displayed across the walls of his studios as inspiration.

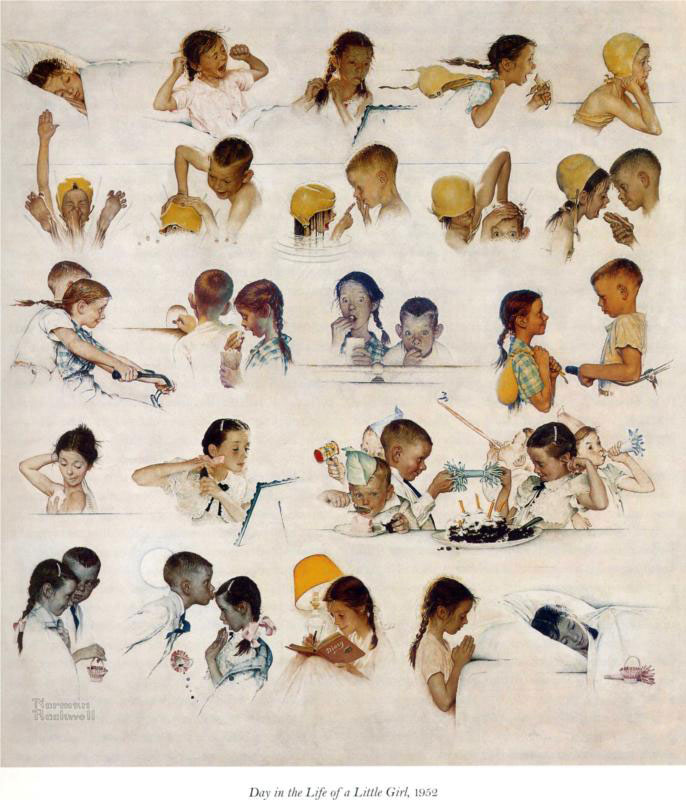

Serving in WWI as an artist, Norman returned to civilian life producing works for various magazines until he eventually found himself painting regularly for the Saturday Evening Post which established his role as the painter of America’s soul for the next five decades. With a passion for capturing universal sentiments even in the microcosm of life, Rockwell found himself pioneering the domain of storytelling by transforming the “fixed” medium of painting into a medium for storytelling.

This focus on painting “outside of the canvas” so to speak set Rockwell apart from all of his contemporaries who were far too fixated on sensual imagery of commercial art or random emotional tones prevalent in the newly emerging abstract art world. Describing his feelings about the schism between “illustration” and “fine art”, Rockwell had this to say:

“No man with a conscience can just bat out illustrations. He’s got to put all of his talent, all of his feeling into them. If illustration is not considered art, then that is something that we have brought upon ourselves by not considering ourselves artists. I believe that we should say, “I am not just an illustrator, I am an artist.”

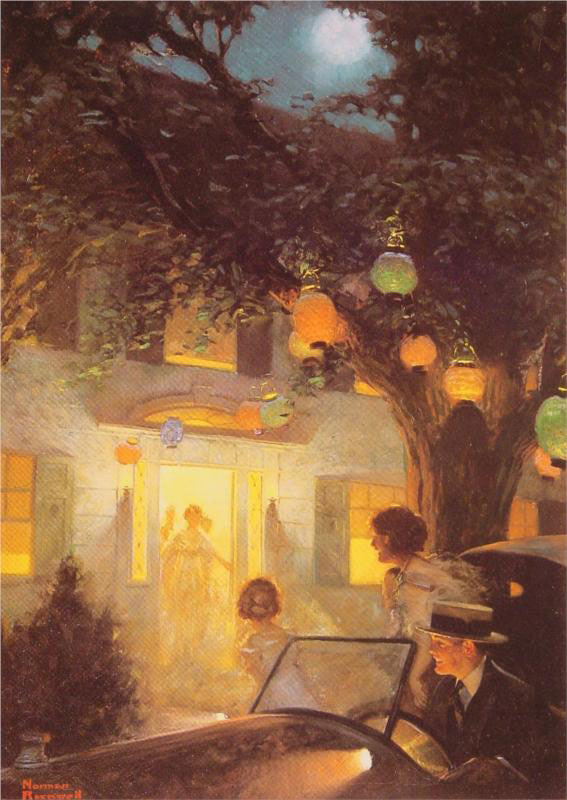

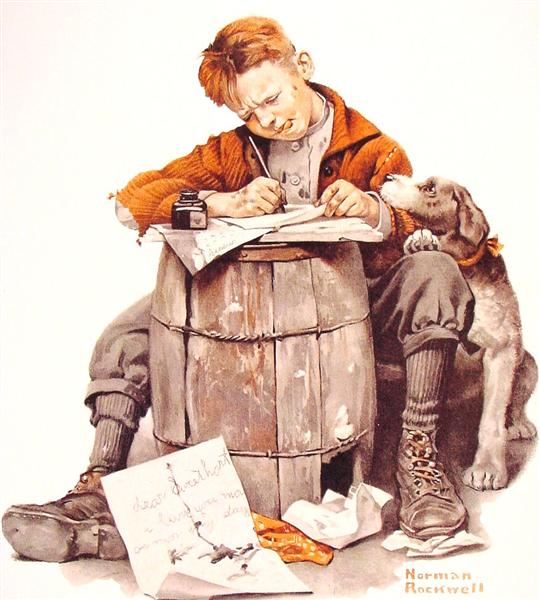

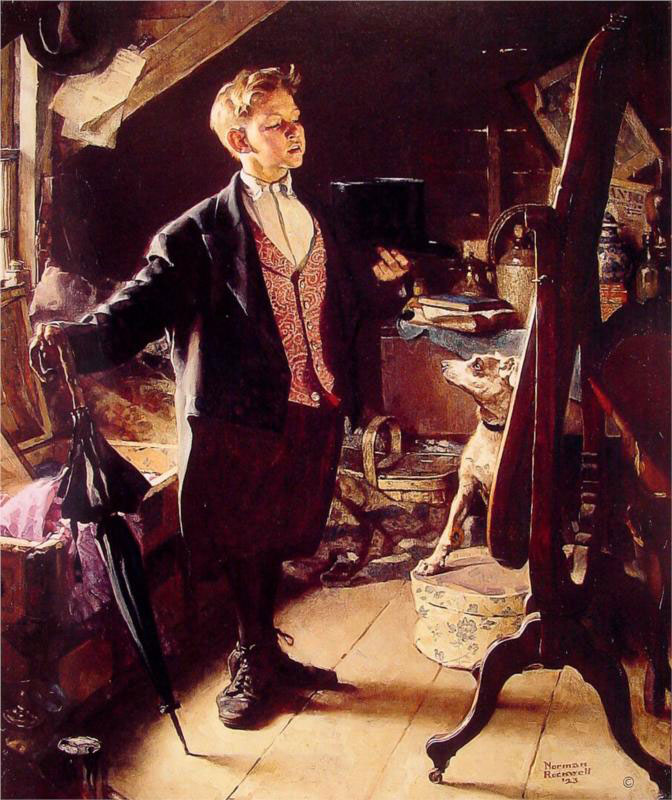

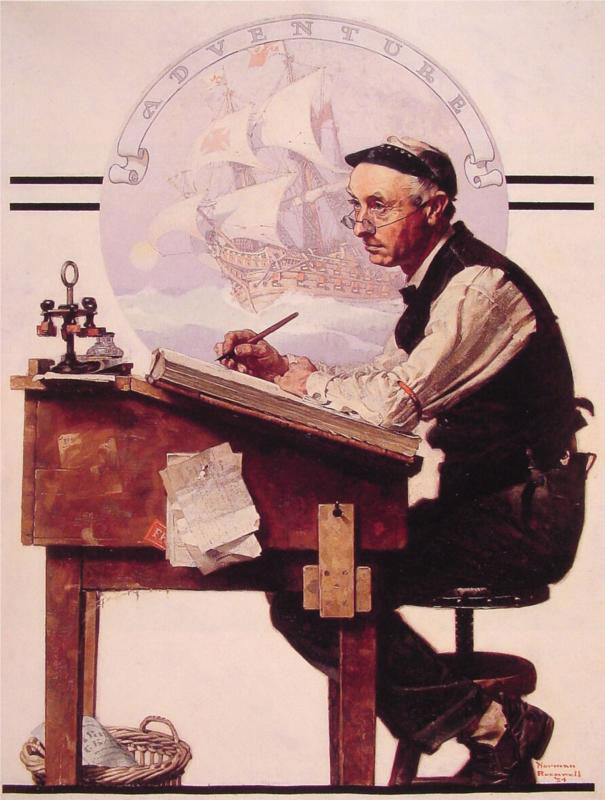

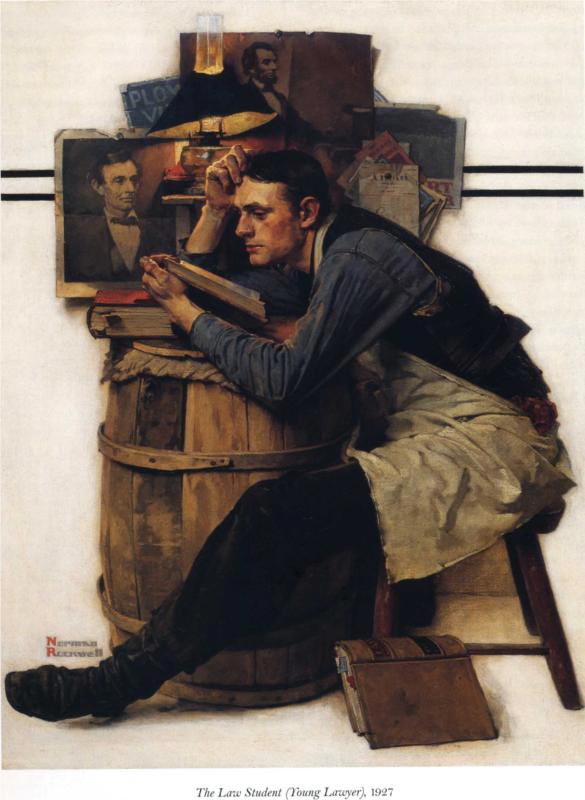

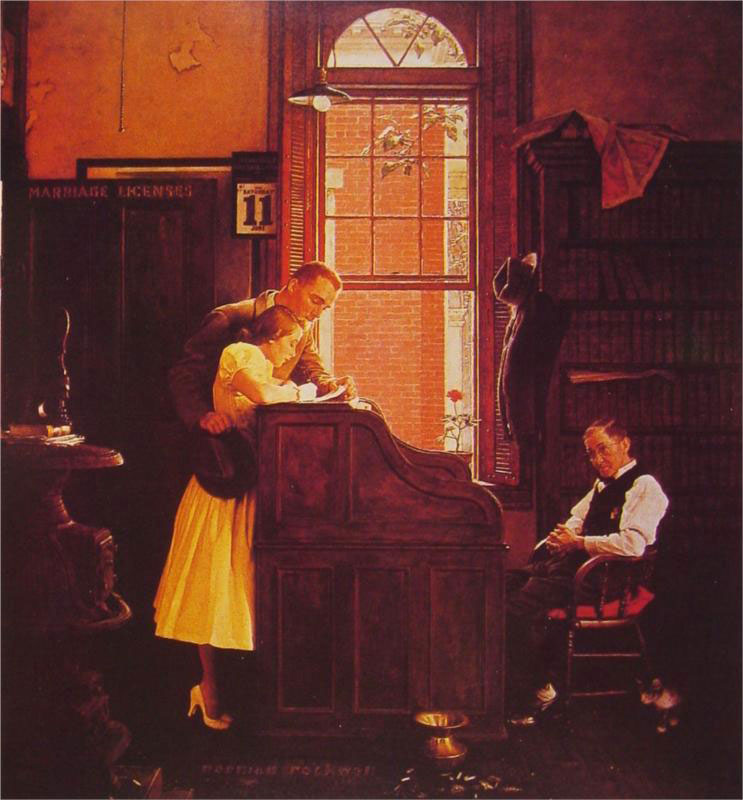

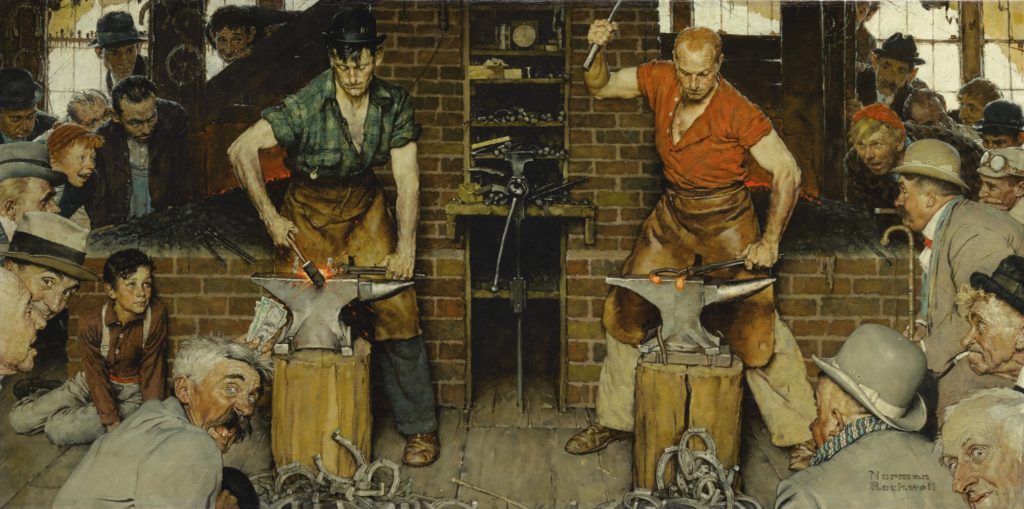

The following gallery showcases samples of his works from his first Post cover in 1916 throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

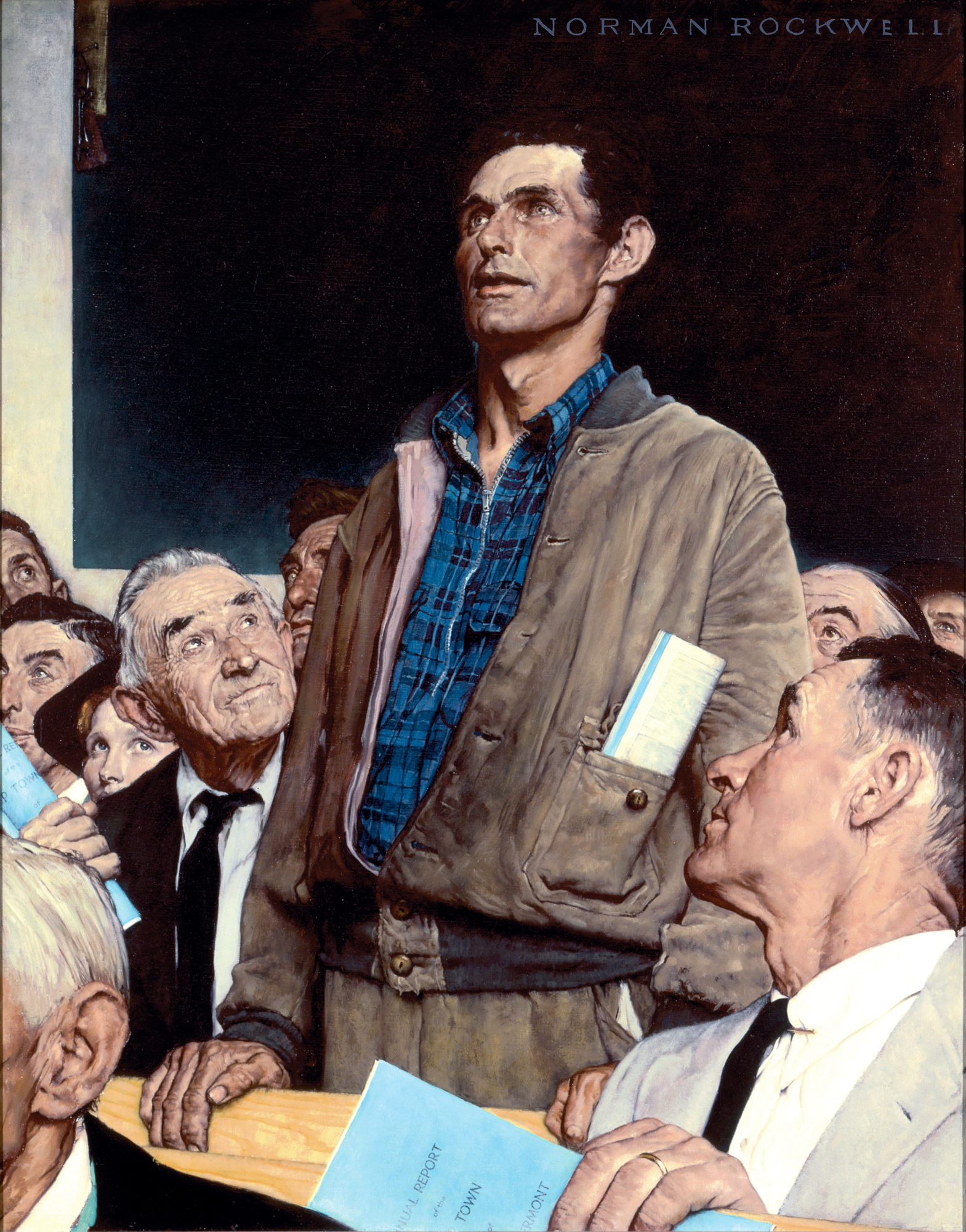

During the course of WWII, Rockwell became passionately inspired by Franklin Roosevelt’s anti-colonial program for the post-war world enunciated in his Four Freedoms speech of 1941 (and which was later embedded into the Atlantic Charter and United Nations). Rockwell had lost many nights sleep trying desperately to conceptualize how such abstract ideas as freedom from want, freedom from fear, freedom of speech and freedom of worship could be expressed visually on canvas.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms masterpieces were run on the covers of four consecutive Saturday Evening Posts along with accompanying essays. When the paintings were showcased across America as part of a Victory Bonds campaign, Rockwell was overjoyed to learn that they had inspired citizens to invest over $130 million of war bonds (the equivalent of $2 billion in today’s dollars). These paintings were a major watershed for Rockwell’s personal evolution, as the artist had been searching for three decades in vain to find a higher meaning towards which his art could be devoted. FDR’s moral vision provided that higher meaning for the first time and the this flame came back repeatedly and with increasing intensity for the rest of his life.

Other famous WWII Rockwell paintings celebrated the role of women who broke all prejudices and expectations by filling the role conventionally held by men in the workforce. Most famous among these paintings are Rosie the Riveter and Liberty Girl both painted in 1943. Rosie the Riveter was directly modeled off of Michelangelo’s Prophet Isaiah on the Sistine Chapel.

Liberty Girl (1943)

Rosie the Riveter (1943)

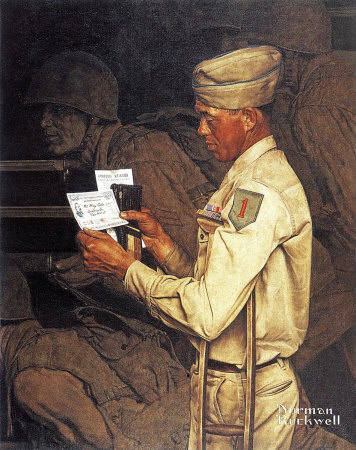

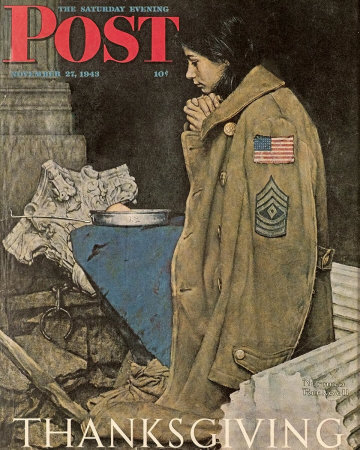

It is interesting to note that not a single cover featured during the war years glorified militarization or violence but rather emphasized profoundly human moral sentiments, and layered stories that conveyed hope, somberness and beauty in the face of the ugliness and tragedy of war.

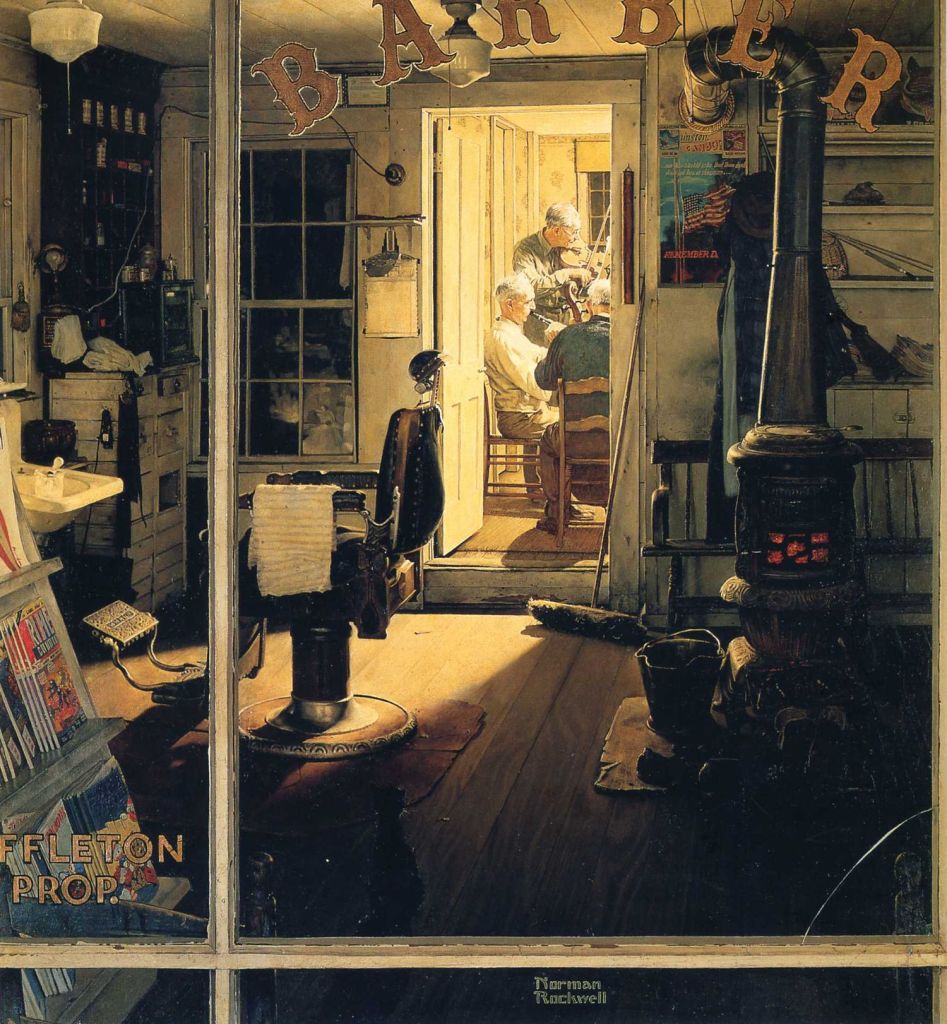

After the war, Rockwell continued to paint regularly for the Post, but gained a new power of moral patriotism which began animating his works. Throughout 1945-1959, many of Rockwell’s greatest pieces which destroyed the artificial barrier separating the worlds of “commercial illustration” and fine arts were accomplished. Paintings such as Shuffleton’s Barbershop (1951) and Saying Grace (1950) represented powerful works which the staunchest art critic would be hard pressed to distinguish from the greatest paintings of the Dutch Renaissance.

Shuffleton’s Barbershop (1951)

Saying Grace (1950)

Describing his own admiration of Rembrandt as the ultimate ideal, Rockwell said:

“To me a Rembrandt painting, any of his paintings, they are like a beautiful symphony. They have these great deep notes. He understood humanity. He’s just the greatest.”

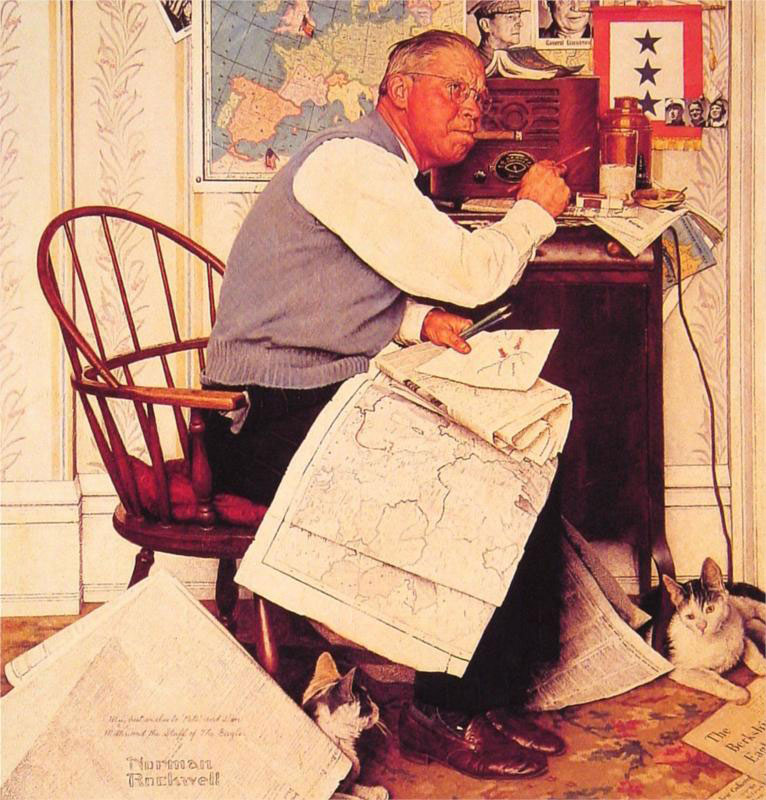

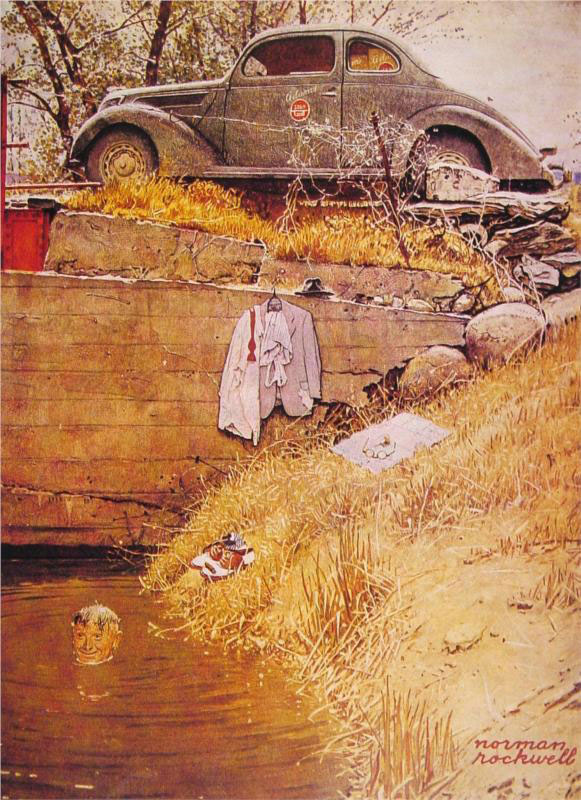

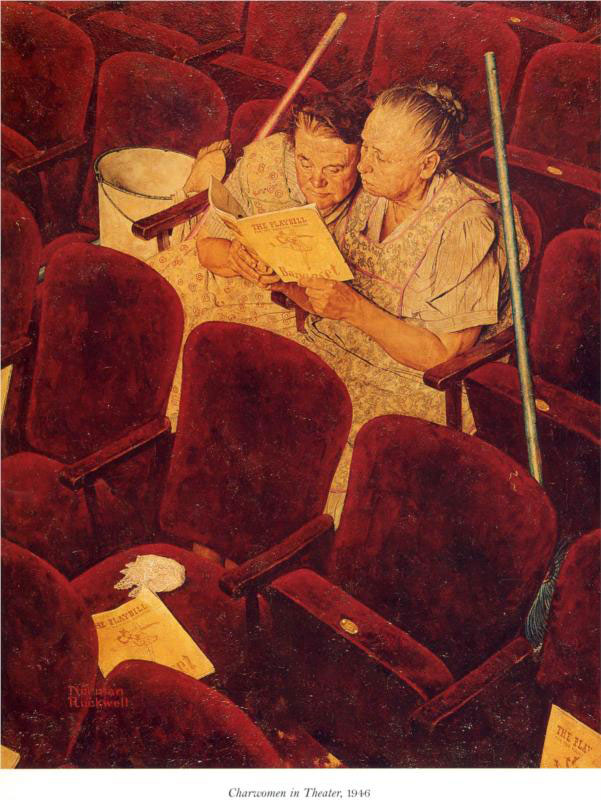

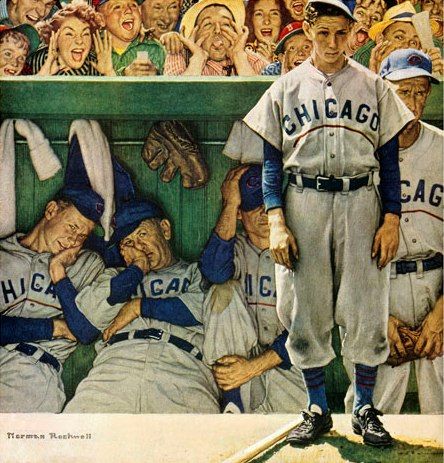

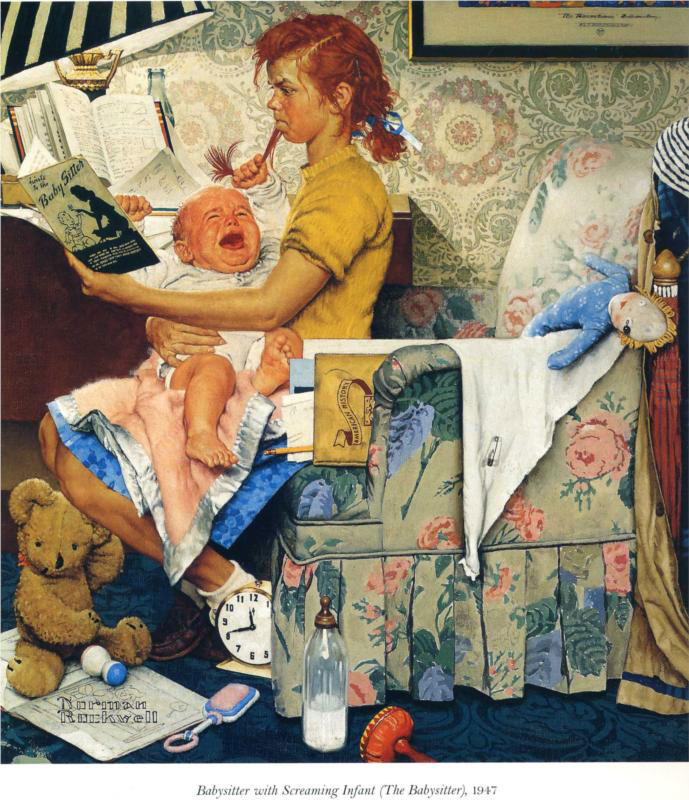

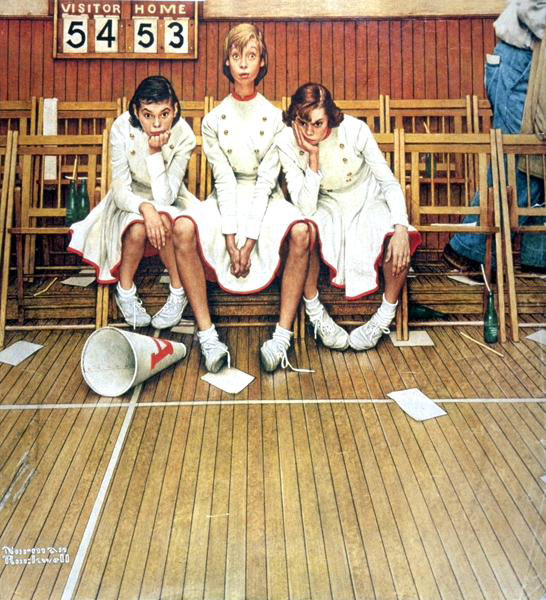

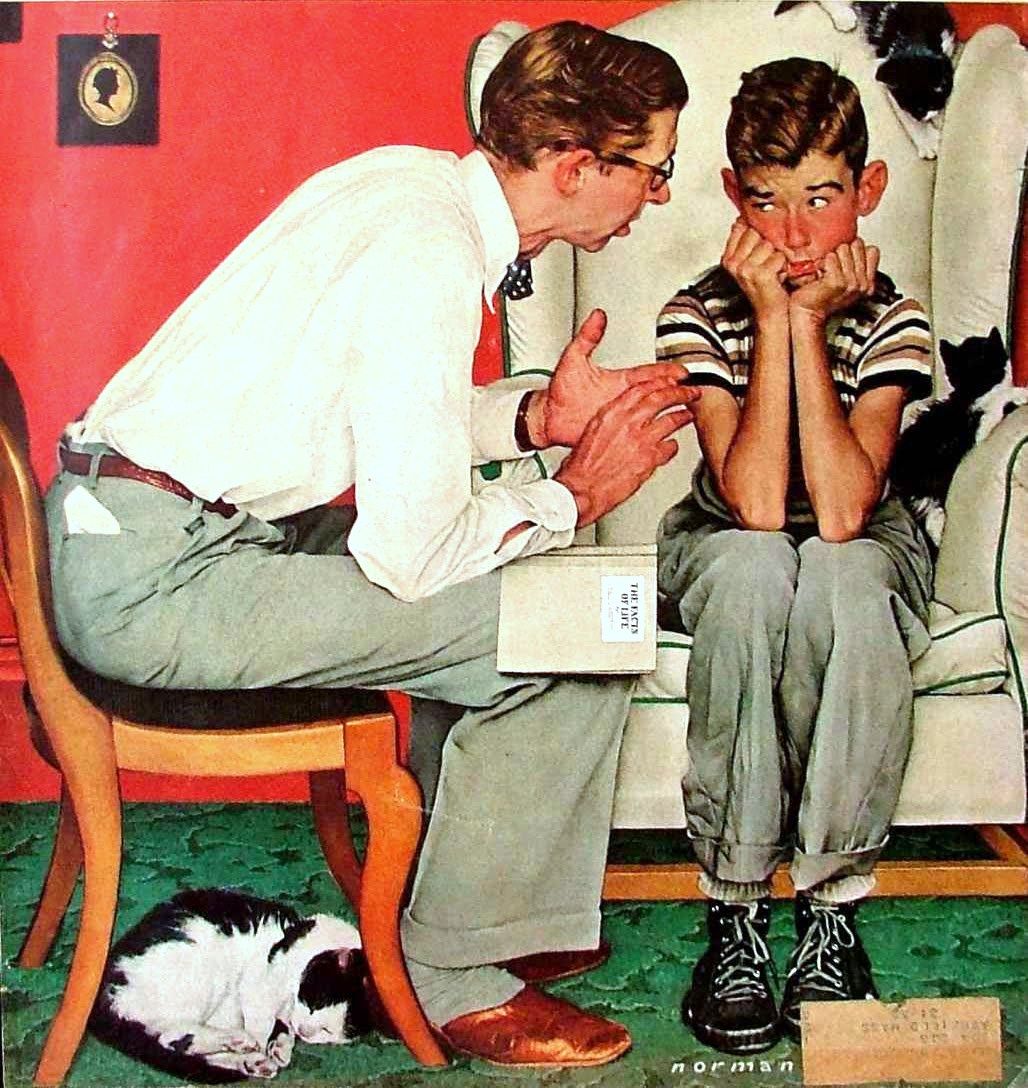

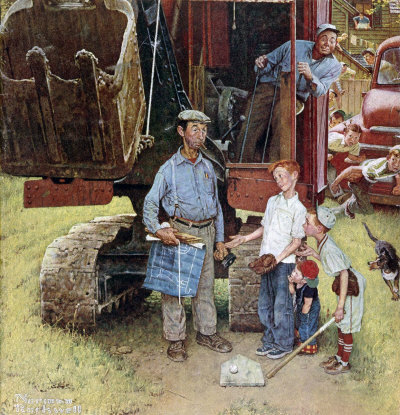

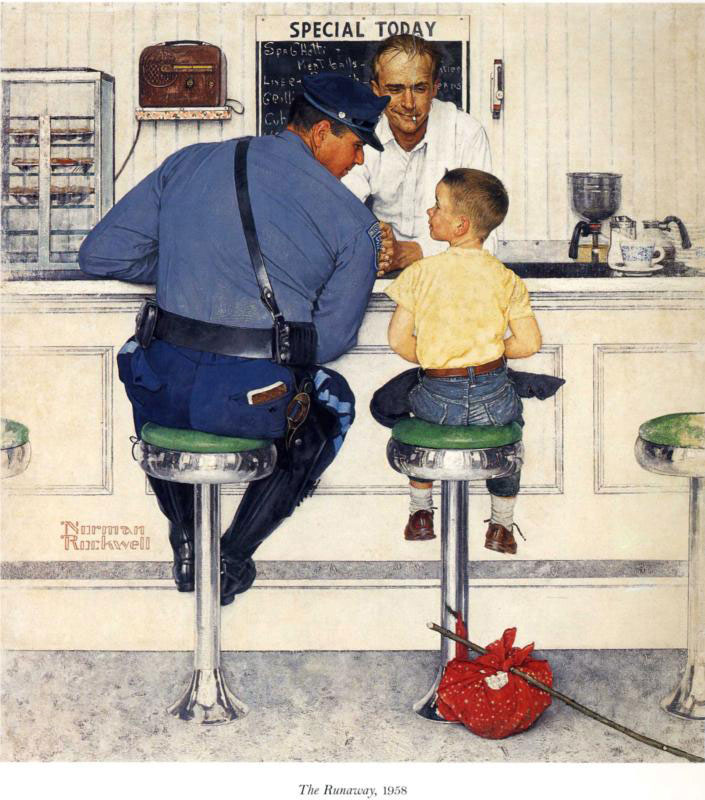

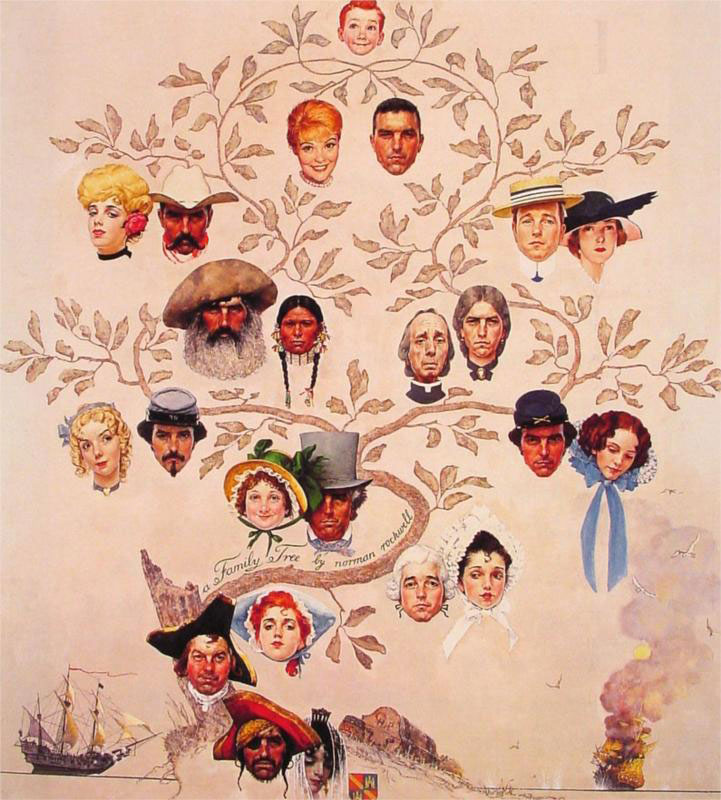

Other paintings of the 1945-1960 period are worth exploring for the maturation of technique and also subtlety of emotional tones, and irony which he excelled at expressing. Also of note, is that with the mysterious fire which destroyed Rockwell’s studio in 1944 (including ALL of his paintings and thousands of costumes and props collected over a lifetime), the artist chose not to wallow in tragedy but saw the disaster as an opportunity to become unshackled by the past. After the fire, Rockwell became more than a painter of quaint scenes or costume pieces and now adopted a more dynamic documentary style, perspectives and action. Many of following 1945-1960 selected pieces illustrate that change remarkably:

Rockwell did not hestitate to take a swipe at the Modernist movement that had taken over the “fine arts” world by this period with his famous ‘painting within a painting’ called The Connoisseur (1962). In this hilarious painting, an anonymous art connoisseur closely inspects a large modern painting executed in the style of “scatterist” Jackson Pollock. In this piece even art critics had to not only admit that Rockwell had perfectly executed Pollock’s style, but also that his method was of an untouchably higher power, as it gave him the capacity to replicate Pollock (but Pollock never had the capacity to replicate Rockwell.) In fact, when American abstract artist Willem de Kooning saw this for the first time in 1968, he said: “Square inch by square inch, it’s better than Jackson!”

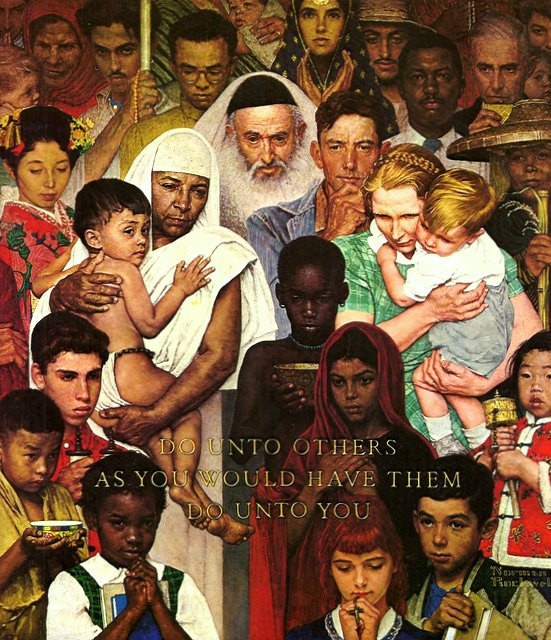

By and large, 1960 was ushered in by both a personal tragedy with the death of his wife Mary in 1959, but also a hopeful transformation of the moral-political order dreamed of by President Roosevelt years earlier as a young President Kennedy arose to power. This new era of cautious optimism and peace was expressed by Rockwell’s powerful painting “The Golden Rule” of 1960.

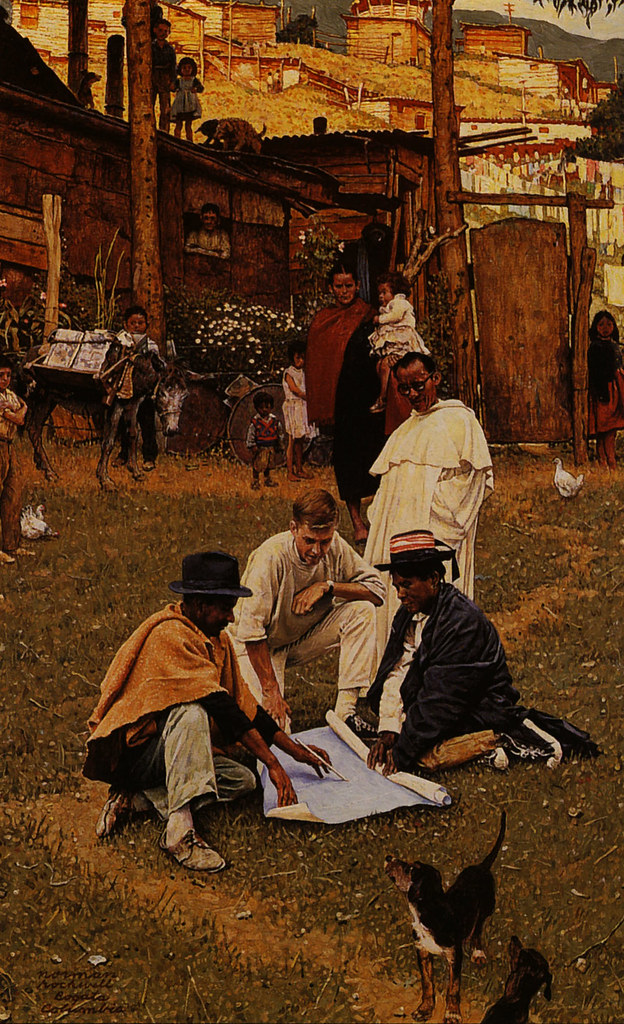

Rockwell was a firm believer in Kennedy’s dream for America and was uplifted by JFK’s Peace Corps which inspired powerful artistic homilies both before and after Kennedy’s murder.

Under the dark clouds of the Cold War and mutually assured destruction, Kennedy challenged Americans to think what they could do for their country and inspired a powerful optimism that made young and old alike believe that hope for a better future was possible. But with the leader’s death on November 23, 1963, Rockwell took on for the first time the uglier side of America which his previous efforts had always avoided.

This break from portraying the purely optimistic America of his ideals took the form of a January 14, 1964 painting commissioned for Look Magazine entitled The Problem We All Live With featuring a young Ruby Bridges being escorted by four state marshals into a desegregated New Orleans elementary school in front of jeering tomato tossing crowds. This painting was complemented by Rockwell’s two other famous works which directly challenged the race problem in America with Murder in Mississippi (1965) and New Kids in the Neighborhood in 1967.

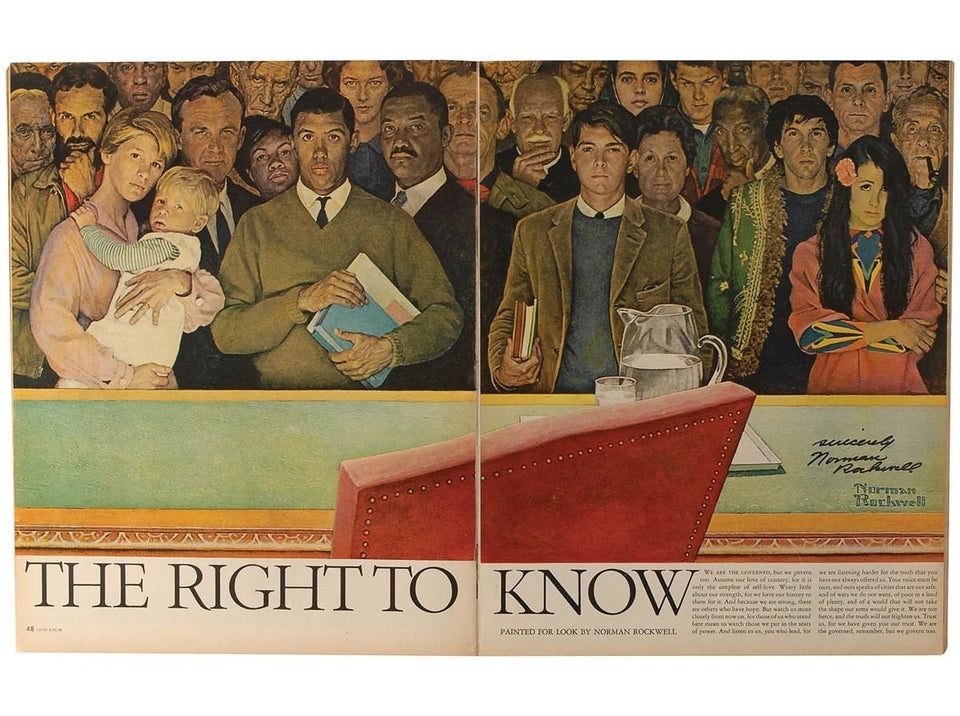

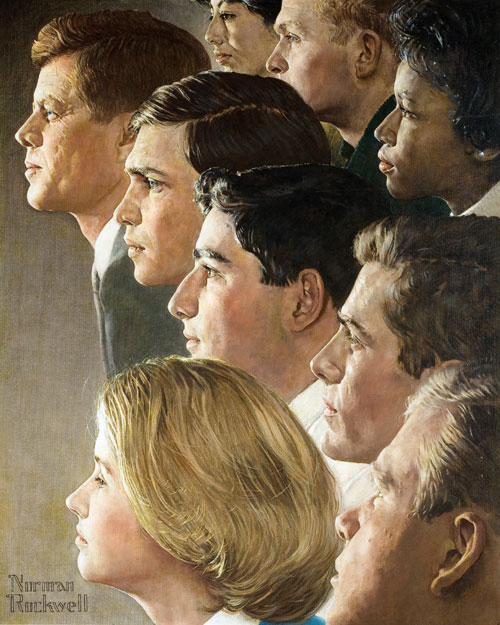

With the wave of assassinations of the 1960s, coinciding with the new war in Vietnam, Rockwell spoke to the inner moral anger and demands for truth felt deeply by the American people with his lesser known 1968 masterpiece “The Right to Know” published in Look Magazine featuring citizens of all ages (including Rockwell himself) looking powerfully upon the viewer, who is identified behind the desk of an anonymous elected official. The soulfull faces deeply troubled in this painting demanding their ultimate right to not be deceived could be seen as the fifth painting of Roosevelt’s Freedom series executed 25 years earlier. By the time Rockwell painted this piece, Americans had watched the murder and cover-up of John Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Bobby Kennedy. Meanwhile in Vietnam, 16 000 American soldiers had already perished.

Although he had put his heart and soul into using his art towards victory in WWII, Rockwell took a stand against the irrational wars of empire that overtook America, turning down a lucrative offer to paint a U.S. Marine recruitment poster in 1966 saying “I just can’t paint a picture unless I have my heart in it.”

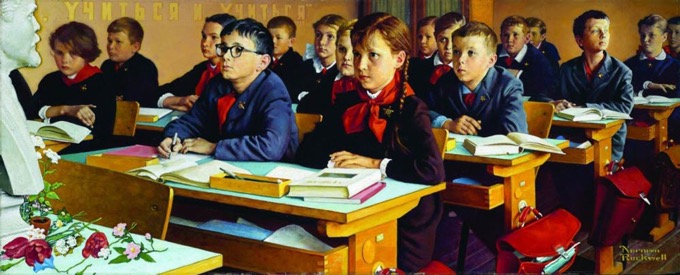

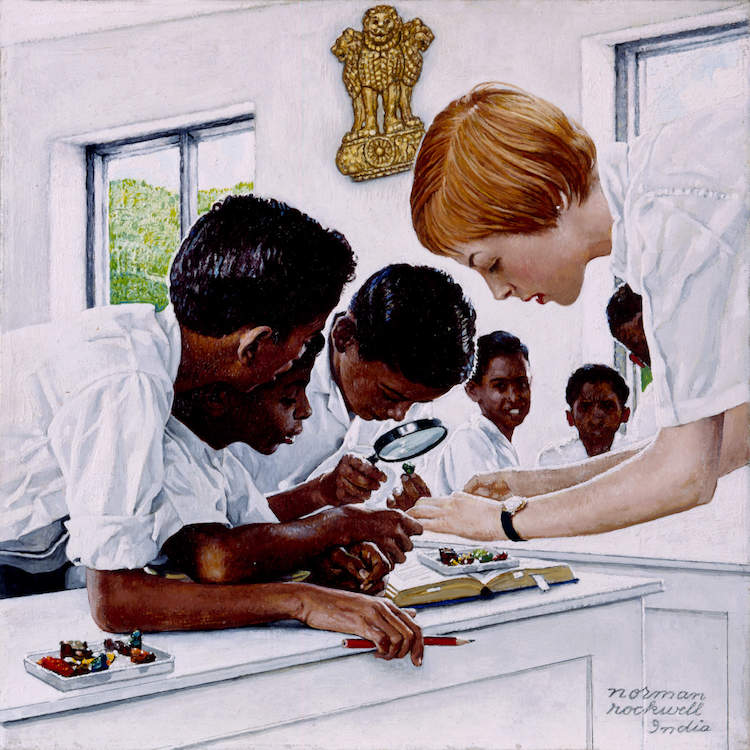

Rockwell recognized the absurdity of the Cold War logic of Mutually Assured Destruction and worked to remind Americans that Russians were just as human with hopes, emotions and children… a fact too often forgotten by traumatized America overfed by anti-communist propaganda. Rockwell was not only a founding member of the National Council of American Soviet Friendship in 1945, but happily took the opportunity to travel to Moscow in 1967 where he humanized the Russian people in his painting of “A School Room in Russia” published in Look Magazine in October 1967.

Rockwell won the ire of many western academics and art critics who had drank the CIA-funded kool aid which claimed that the “art of democracy and capitalism” was embodied in Abstract modernism while only communists and totalitarians believed in realism or purposefulness in art. Standing against the hegemony of abstraction Rockwell stated his preference for Russian aesthetics:

“I’m like the Russian artists. I believe in things… Our modern art is to a great extent decadent. But they communicate an idealism. Their art has a constructive viewpoint. At least in terms of their own country. Doesn’t the picture of a healthy woman worker do more good than a picture of a woman all broken into pieces or the disordered mind of the artist?”

Focusing much of his energy into the ideals of brotherhood and cooperation, Rockwell recognized that the means of actualizing that goal was made possible through the mission set forth by John F. Kennedy who challenged America to go to the Moon and beyond in his famous 1962 speech at Rice University. To this end, Rockwell’s NASA commissions are an immortal contribution to space art as the opening up of a new school of painting echoing the earlier Hudson River School that had found its artistic inspiration in the principle of Manifest Destiny beyond the horizons in the 19th century.

Today our society has been given yet another opportunity to take hold of the dream for an age of brotherhood, cooperation and space exploration which John F. Kennedy envisioned. Artists across the world have no choice but to confront that new possibility of an optimistic future and after confronting it, either find inspiration from it’s existence, or continue to adhere to the cynical, mis-anthropic view of humankind which the Cold War and CIA-funded abstract art created in the post WWII era.

Whether or not artists choose to acknowledge this reality does not change the objective fact that each of us has been endowed with certain creative powers and also the moral responsibility to use those powers for the good of ourselves, our nation and all of humankind- as Rockwell understood all too well.

Matthew Ehret is the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Patriot Review and has authored 3 volumes of ‘Untold History of Canada’ book series. His works appear regularly on The Duran, Strategic Culture, Sott, Fort Russ, Zero Hedge, Global Times, L.A. Review of Books, LeSaker.fr, Vigile Quebec, South Front and Veterans Today. He is a correspondent/BRI Expert for Tactical Talk. In 2019 Matthew co-founded the Montreal-based Rising Tide Foundation. He can be reached at matt.ehret@tutamail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.