July/August 2019

By Eric Brewer and Richard Nephew

Since Iran’s May 2019 announcement

that it would no longer abide by some nuclear restrictions under the Joint

Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the Trump administration has sought to

push back against these moves by citing the imperative of the JCPOA’s

constraints. The JCPOA created limits on Iran’s nuclear fuel cycle that mean

Tehran would need a year to produce enough nuclear material for a bomb, and the

agreement established enhanced transparency and inspector access throughout the

entire fuel cycle.

U.S. National Security Advisor John

Bolton speaks to reporters at the White House April 30. Bolton has linked any

Iranian expansion of enrichment activities to a deliberate attempt to shorten

the breakout time to produce nuclear weapons. (Photo: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty

Images)

The U.S. push for Iran to adhere to

the deal’s terms has drawn some international incredulity given how the United

States withdrew from agreement in May 2018 while noisily alleging many JCPOA

flaws. More subtly, the Trump administration has begun to lay the groundwork

for what can be described as its first real redline for the nuclear program:

that any reduction in Iran’s one-year breakout timeline, the amount of time

Iran would need to produce enough enriched uranium for a bomb, is unacceptable.

It is unclear how much reduction the

administration would tolerate, what its response would be, and given President

Donald Trump’s avowed preference for a deal and to avoid another conflict in

the Middle East, whether it would be enforced at all. Yet, National Security

Advisor John Bolton in late May linked any Iranian expansion of enrichment

activities to a deliberate attempt to shorten the breakout time to produce

nuclear weapons, which would suggest that a severe response, perhaps even military

force, would be on the table to prevent Iran from a nuclear restart. At the

very least, the United States is shifting the traditional definition of what is

unacceptable from a weapon or having the ability to produce one quickly to any

deviation from JCPOA baseline restrictions.

A renewed nuclear crisis with Iran is

now likely. Not only would Iran’s announced steps from May shorten the breakout

timeline, only modestly at the start, but Iran has set a deadline that expires

in early July for the restart of other nuclear activities that might reduce the

timeline considerably faster.

Nevertheless, Iran’s nuclear actions

so far do not merit this redline or the military response that could follow,

nor do they rise to the level of an unacceptable threat to the United States or

its interests. Rather, they are a signal that, although some in the Trump

administration believe otherwise, Iran will not consent to being pushed via

sanctions without seeking leverage of its own.

To be fair to the Trump

administration, there is some utility in setting out a clear marker for Iran as

to what constitutes unacceptable nuclear behavior. In fact, one of the biggest

concerns over Trump’s Iran policy thus far is that the Iranians have seen

little clarity from the White House as to what the United States wants from

Iran. U.S. objectives have varied over time and, depending on who is

articulating the policy, have involved everything from regime change to a

renegotiated JCPOA. It would be valuable to give Iran and the rest of the world

a clearer sense of U.S. intentions, expectations, and the seriousness with

which the United States would treat certain Iranian nuclear actions. A firm

stance now could also potentially head off a more dangerous situation down the

road, and for the Trump administration, there is a palpable desire to avoid

being identified as the cause of this new nuclear crisis.

Despite these potential benefits, the

particular redline that appears to be in the process of being established is

profoundly unnecessary, unwise, and dangerous for four reasons.

Iran’s Restart Will Be Gradual

First, establishing the one-year

breakout timeline as a redline makes little sense in terms of the nuclear

program itself. The JCPOA was designed to give governments at least a year to

mount a strategy to react if Iran started to exit its obligations and dash to a

weapon. For this reason, the JCPOA built in restrictions on Iran’s centrifuges,

its uranium stockpile, and spare parts and materials for the program, as well

as intrusive transparency steps that ensure the International Atomic Energy

Agency (IAEA) and the international community would quickly become aware of any

deviation from Iran’s agreed steps.

Iran has said it will expand its

enrichment of low-enriched uranium (LEU) and heavy water and will consider

additional steps as well, perhaps as soon as July 6. Iran’s decision to restart

these nuclear activities will eventually erode the breakout time barrier of a

year, but this will occur, at least at the start, relatively slowly and

incrementally. The reasons are political and technical. Politically, Iran’s

main goal is to regain negotiating leverage and force Europe to provide

economic benefits or risk the deal falling apart, not to race to a bomb. As

Iran has done in the past, it will likely calibrate the pace and scope of its

nuclear activities based in part on how the international community responds.

From a technical standpoint, Iran’s

enriched-uranium stockpile will probably expand gradually. Iran has said it

will exceed the JCPOA’s 300-kilogram limit by June 27, which IAEA reporting

suggests would be a major increase in the pace of enrichment operations but not

impossible. That said, even at the rate of enrichment that this would suggest,

as much as 30 to 50 kilograms per month, it would take many months before Iran

would have enough LEU, which would need further enrichment, for a bomb. Of

course, enriching uranium further from its current level would be noticed by

the IAEA and time consuming.

Iran’s buildup of heavy water is less

concerning from a nuclear weapons perspective. Even if Iran fulfills its threat

to abandon its JCPOA-mandated requirement to redesign the Arak reactor to

produce less plutonium in July, the path to actually completing and starting

its old reactor design would be a long and uncertain one.

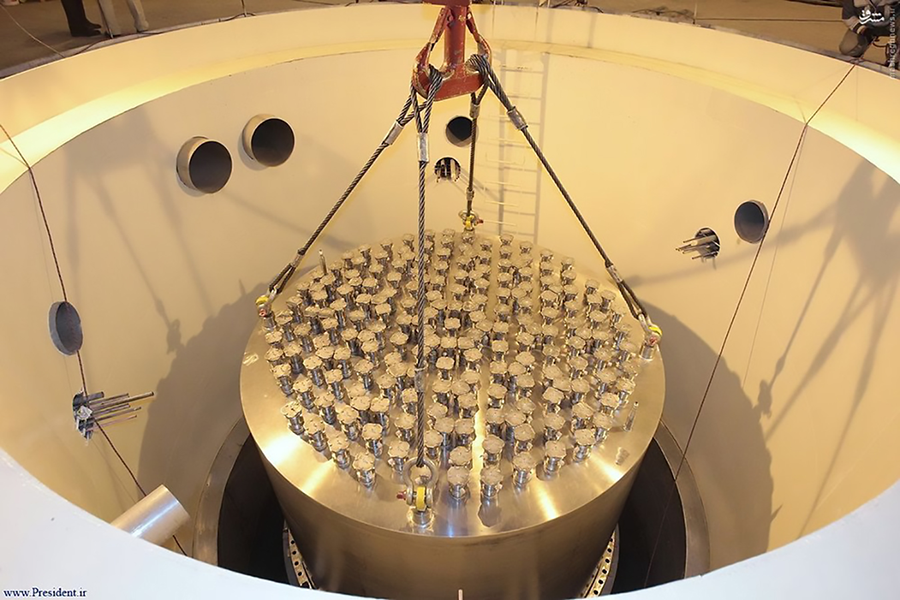

In early 2016, the IAEA confirmed

that Iraq had removed the core of its heavy-water reactor at Arak, as required

by the 2015 nuclear deal. Restoring the reactor to maximize its

plutonium-production capability would be a lengthy process. (Photo: President of

the Islamic Republic of Iran)

More worrying would be if Iran acts

on its threat to increase enrichment levels as early as July. Depending on how

high Iran goes, such as resuming enrichment to near 20 percent uranium-235,

this could have a seriously adverse affect on Iran’s breakout timeline as this

material accumulates. A U.S. decision to end sanctions waivers that allow Iran

to import 20 percent-enriched fuel for its research reactor would make

it easy for Tehran publicly to justify higher enrichment.

it easy for Tehran publicly to justify higher enrichment.

Some of these steps are more

concerning than others, but none would indicate a breakout, and they do not

suggest that the world is facing an imminent Iranian nuclear weapons threat.

Indeed, unless Iran starts to curb IAEA access, which in and of itself would be

a major concern, all of these measures will be done in full view of inspectors,

which is exactly how Iran wants it. There is time to resolve the crisis

diplomatically before using military force. A year was judged to be a

reasonable but not necessarily minimum amount of time to do so. Indeed, prior

to the JCPOA, Iran only needed a few months to produce a bomb’s worth of

material. Even then, the United States determined that it could stop an Iranian

breakout with the use of force if necessary.

An Ambiguous Redline

Second, for this redline to work,

Iran would have to know when it is nearing that threshold so that if it wants,

it can refrain from doing so. Because Iran possessed a large LEU stockpile, not

to mention its near 20 percent-enriched uranium, for many years prior to the

JCPOA, Iran may not perceive its renewed possession of this material as now

representing a casus belli for Washington. In fact, Israel

even set a redline for Iran’s enrichment program that could be interpreted to

permit up to 200 kilograms of near 20 percent-enriched uranium, suggesting that

what Iran is presently doing is far below the Israeli threshold for action.

Moreover, breakout timelines are

based on a range of assumptions, and even among U.S. allies, there was some

ambiguity about those timelines as the JCPOA was negotiated. It is therefore

unlikely that Iran and the United States would have a common definition of

where that tipping point occurs. This presents a high risk of miscalculation.

Advocates of Trump’s redline approach

may believe that this works to the U.S. advantage: by laying out extreme

positions, Iran can be deterred from undertaking any nuclear expansion. This

view, however, ignores two facts. First, Iran will judge what is tolerable to

the West based on past experience, and higher levels and amounts of uranium may

not be seen as such. Second, Iran’s perspectives on U.S. deterrence are

informed by the full range of U.S. responses to Iranian behavior. With North

Korea and Iran, Trump has a history of issuing grand yet vague threats and then

not following through on them, a practice that is likely to undermine U.S.

credibility on this redline. In addition, Trump’s own attempt to walk back his

administration’s hawkish stance toward Iran in late April and early May with

respect to the deployment of U.S. forces in the Persian Gulf has likely

confused the Iranians. Offers to restart negotiations on a more limited slate

of issues than U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s “12 demands”—a list he

laid out in May 2018 for Iran to fulfill, including elimination of its nuclear

fuel cycle, severe restrictions on its missile program, and the end of its

relationships with Hezbollah and other proxies—probably have done likewise. It

certainly has led Iran to try to convince Trump that he is being manipulated

into conflict via the “B team,” a term Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif has

used to describe those he says are war advocates, including Bolton, Emirati

Crown Prince Mohammad bin Zayad, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, and

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Even in the likely event that this

ploy fails, the dynamic means that Iran is unsure as to where the president

stands in all of this. In such an atmosphere of confusion and ambiguity,

dangerous mistakes can be made by both sides.

Fewer Peaceful Options

Of course, Trump administration

officials and their advocates may stress that no one has mentioned the word

“force” in any official capacity and that this is a conclusion being

inappropriately drawn. Yet, the third problem with the redline approach being

articulated is that Trump administration actions have reduced the scope of

nonmilitary responses. Most options short of war have already been expended by

this administration and arguably are why this predicament exists in the first

place. This includes walking out of the JCPOA and reimposing and expanding

sanctions.

Some additional sanctions could be

imposed against Iran. Recent actions, such as designations of Iranian

petrochemical companies and sectoral sanctions targeting other activities, such

as Iran’s metal sector, may help U.S. sanctioners build momentum against Iran.

Their value as a deterrent to Iran increasing its nuclear activities, however,

is limited because the administration is already aggressively seeking to

eliminate Iranian oil exports and has implemented widespread financial

sanctions, which are far more damaging measures. If history is a guide, more

pressure will likely cause Iran to accelerate its program if there is no

realistic diplomatic off-ramp. At this point, Iran’s apparent calculus is that

there is little more that Washington can do to punish Tehran from pushing back

against the United States by rolling back its JCPOA commitments, at least in

part and in stages. Iran sees very little difference between the sanctions

pressure Washington is applying now and what more it could generate if Iran

builds up its nuclear program. Without this perception, Iran would not have

broken a year’s worth of restraint to act now.

The absence of specific and discrete

response options for enforcing the redline runs the risk of creating a hollow

commitment on the part of the United States. As the United States has learned

to its chagrin in recent years, unenforced redlines carry risks and

consequences. In this case, it would make it more difficult for the United

States to deter Iranian nuclear threats that really do matter in the future.

The United States would be ill advised to issue such pronouncements and fail to

make good on the promises inherent within them. This is why setting

appropriate, sober, and well-considered redlines, if redlines are set at all,

is so imperative.

A Bigger Risk Ignored

Finally, although what Iran is doing

to retaliate for the U.S. pressure campaign may ultimately create some breakout

risk, a redline focused on protecting a one-year breakout timeline focuses on

the wrong part of the problem. Iran’s most plausible and likely weapons

development scenario would involve a covert program rather than relying

exclusively on its known facilities and materials. Iran knows that IAEA

oversight, enhanced by the JCPOA, enables rapid detection of any major steps

toward breakout. Even if Iran is able to erode breakout time to the

two-to-three-month range that predates the JCPOA, this is still sufficient time

for the United States to detect and respond militarily, and Iran knows it.

For these reasons, the most important

step the United States can take to prevent moves toward a nuclear weapon using

the very facilities and materials about which Bolton is now concerned would be

to ensure the transparency and monitoring of Iran’s nuclear program that the

JCPOA provides. These same transparency and monitoring tools that help detect a

breakout can give confidence that Iran is not presently in possession of covert

facilities and that they would be detected long before they can deliver a

nuclear weapon.

A Better Approach

The United States does need to

demonstrate its readiness to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. For

this reason, showing a willingness to use all the means of U.S. power,

including diplomacy, to prevent such an eventuality is reasonable and prudent.

Indeed, diplomacy is the only means that the United States has employed in the

last two decades that has proven capable of limiting Iran’s nuclear program to

a significant degree and for a sustained period of time.

Trump has repeatedly said that he

wants a better deal than the JCPOA. It is an ambition that people across the

political spectrum can endorse, but it seems unlikely that a significantly

better deal is available in the current climate. A better deal will not come

from issuing ill-founded redlines that increase the risk of miscalculation

while targeting the wrong threats. Rather, the Trump administration should

invest itself in developing a realistic negotiating agenda and getting back to

the table with Iran to avoid this crisis while it still can.

Eric

Brewer is a fellow

and deputy director of the Project on Nuclear Issues with the Center for

Strategic and International Studies in Washington. He served a decade in the

U.S. intelligence community, including as deputy national intelligence officer

for weapons of mass destruction with the National Intelligence Council. Richard

Nephew is a senior research scholar with the Center on Global Energy

Policy at Columbia University. He has held positions at the Department of

Energy and Department of State and on the National Security Council.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.