Authored by Kelsey Davenport and

Daryl Kimball on July 9, 2019

With Further Nuclear Moves, Iran

Seeks to Leverage Promised Sanctions Relief

Iran announced July 8 that it

has started enriching uranium at levels in excess of the limit of 3.67 percent

uranium-235 set by the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan

of Action (JCPOA).

The move is the second troubling

retaliatory measure in two weeks by Iran to walk back its compliance with the

JCPOA. Last week, Iran exceeded the 300-kilogram limit of its stockpile of low

enriched uranium set by the JCPOA.

Iran’s moves to curtail compliance

with the JCPOA have long been expected. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said May 8 that Iran would no longer be bound by the

300-kilogram LEU cap and would exceed the cap on enrichment levels in 60 days

if the remaining parties to the nuclear deal did not deliver on sanctions

relief.

Iran announced July 1 that it breached the 300-kilogram limit on

uranium gas enriched to 3.67 percent (202 kilograms of uranium by weight) and

the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) later confirmed that Iran has exceeded the limit.

While Iran’s actions clearly violate

the deal, a slight excess of uranium enriched to 3.67 percent does not pose an

immediate proliferation risk or significantly reduce the time it would take

Iran to produce enough weapons-grade material for one bomb—which is 12 months

or more as a result of the combined limits established by the JCPOA. After

that, it would take Iran additional time to fabricate a core, fit it with an

explosives package, and integrate it into a delivery system. (See our fact

file, “In

Perspective: Iran and Steps Necessary to Build a Nuclear Bomb.”)

As such, the Iranian actions do not

appear to be an attempt to race to acquire nuclear weapons, but rather a

calibrated effort to secure economic relief Iran was promised by the other

parties to the JCPOA.

The spokesperson for the Atomic

Energy Organization of Iran, Behrouz Kamalvandi, said July 7 that Iran notified the IAEA of its

intentions and will begin the process of increasing enrichment above 3.67

percent “within the next few hours.” Kamalvandi announced July

8 that the level

of Iran’s uranium enrichment has surpassed the 4.5 percent level.

On July 5, Ali Akbar Velayati, an adviser to Iran’s Supreme

Leader, suggested that enriching to a level of five percent was necessary

for electricity generation at the Bushehr power plant. Other Iranian officials

had previously referenced increasing enrichment levels to five percent

uranium-235 and to 20 percent uranium-235. Iran enriched uranium to 20 percent

before the JCPOA, ostensibly for its Tehran Research Reactor, but currently has

no practical need for uranium enriched to either five or 20 percent.

The fuel for Iran’s civil nuclear

power reactor at Bushehr is provided by Russia and the JCPOA ensures that Iran

can import uranium fuel enriched to 20 percent in specific amounts for its

Tehran Research Reactor. The United States has, for now, waived sanctions

allowing fuel transfers for both reactors to continue.

But the extent of the proliferation

risk depends on how many centrifuges Iran begins to use for higher-level

enrichment and how much of the material produced is stockpiled. If Iran

produces and stockpiles uranium enriched to either level, it would begin

to shorten Iran’s so-called breakout time, or the time it takes to produce

enough nuclear material for a bomb, which currently stands at about 12 months.

It does not appear that Iran intends

to resume work on the unfinished Arak reactor at this time. President Rouhani

initially said May 8 that Iran may restart work at the reactor based on its

original design, which would have produced enough plutonium for about two bombs

per year.

However, on July 3 he

stated that

if the remaining parties to the deal meet their JCPOA obligations to assist in

modifying the reactor, Iran will refrain from breaching its obligations on

Arak. At a June 28 meeting of the JCPOA’s Joint Commission, the parties

discussed the positive progress on Arak. (See below for details.)

While the remaining parties to the deal

(China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the EU) have condemned

Iran’s decision to breach JCPOA limits, they appear committed to resolving the

disputes within the JCPOA.

French President Emmanuel

Macron said July 6 that Rouhani agreed to explore

“conditions to resume dialogue” on Iran’s nuclear program by July 15, and

Macron dispatched a personal diplomatic representative, Emmanuel Bonne, for

talks today and Wednesday in Tehran to attempt to dial back the situation.—KELSEY

DAVENPORT, director for nonproliferation policy, with DARYL G. KIMBALL,

executive director

The remaining P4+1 parties to the

JCPOA all expressed regret over Iran’s decision to breach the uranium stockpile

and the 3.67 percent uranium enrichment threshold and urged Tehran to refrain

from further actions that violate the accord. In a July 2

statement, the

foreign ministers of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom and the High

Representative of the European Union, stated that “our commitment to the

nuclear deal depends on full compliance by Iran” and said Tehran’s action

“calls into question an essential instrument of nuclear nonproliferation.”

EU's Foreign Policy Chief

Federica Mogherini, French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, German Foreign

Minister Heiko Maas and Britain's Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt at EU

headquarters in Brussels, May 13, 2019. (Photo: FRANCOIS LENOIR/AFP/Getty Images)

The ministers said they are “urgently

considering next steps under the terms of the JCPOA,” in coordination with the

other parties. That could include invoking the dispute resolution set up by the

deal, although the ministers did not reference that process specifically (see

below for details.)

Russia and China more explicitly

referenced Tehran’s decision as a reaction to the U.S. sanctions campaign. Geng

Shuang, the spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, said “U.S. extreme pressure is the root cause” of the

current tension and emphasized that Iran’s actions are reversible. He called on

all parties to exercise restraint and seek to resolve the issue. Russian

Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated that U.S. sanctions “forbade anyone to buy

excess low-enriched uranium” and contributed to Iran’s stockpile growth.

Under the JCPOA, Iran can remain

below the 300-kilogram limit by downblending enriched uranium to natural levels

or transferring it out of the country. However, in May 2019, the United

States announced it would no longer waive sanctions on the

transfer of enriched uranium. Iran has referenced the U.S. decision as impeding

Tehran’s implementation of the JCPOA.

The White House Press Secretary issued a

statement July 1 stating

that “maximum pressure on the Iranian regime will continue until its leader

alters their course of action” and that it was a “mistake” to allow Iran to

enrich under the JCPOA. The statement called for restoring “the longstanding

nonproliferation standard of no enrichment for Iran.”

A July 1

statement from

the State Department made a similar reference, implying that the enrichment

prohibition on Iran is derived from an international standard. The United

States has long sought to prevent the spread of uranium enrichment and

plutonium reprocessing technologies, but that there is no agreed-upon

international standard of “no enrichment for Iran.”

Many states, including Iran, argue

that there is a “right” to enrichment and reprocessing technology under Article

IV of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Non-nuclear weapon states do

have a right to peaceful nuclear technology under the NPT, but the treaty does

not specify whether or not that includes enrichment and reprocessing.

Past UN

Security Council resolutions demanded that Iran “suspend” its uranium

enrichment program, and imposed sanctions on Iran. Those provisions were

designed to push Iran to negotiate over its nuclear activities and cooperate

with the IAEA’s investigations into past illicit nuclear activities—all of

which Iran has done as part of the JCPOA. Furthermore, the previous UN Security

Council resolutions relating to Iran were modified by UNSC Resolution 2231,

which recognized and endorsed the JCPOA, which allows Iran to enrich uranium

according to strict limitation and increased IAEA monitoring.

For now, the remaining parties to the

JCPOA – China, the European Union, France, Germany, Russia, and the United

Kingdom—are pressing Iran to exercise restraint and continue to cooperate fully

with the IAEA but they are not yet seeking to formally reimpose UN and EU

nuclear-related sanctions and end their support for the JCPOA.

![U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo attends the UN Security Council meeting on Iran, December 12, 2018. [State Department photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain]](https://www.armscontrol.org/sites/default/files/images/P5Alerts/USStateDept-UNSC-PompeoDec2018.jpg)

U.S. Secretary of State

Mike Pompeo attends the UN Security Council meeting on Iran, December 12, 2018.

[State Department photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain]

If Iran continues to exceed other key

JCPOA limits, however, some of the JCPOA states parties may consider doing so.

This could trigger the JCPOA’s dispute resolution mechanism that could be

utilized to resolve acts of noncompliance with the agreement.

According to the process laid out in

the JCPOA (main text,

paragraphs 36 and 37),

any state party that believes another state is not meeting its obligations

under the deal can refer the issue to the JCPOA’s Joint Commission. The Joint

Commission is comprised of the parties to the deal, including the EU, and meets

quarterly to oversee its implementation. The United States, having withdrawn

from the JCPOA, is no longer a state party.

The process detailed in the JCPOA

states that:

- The Joint Commission has 15 days to resolve an

issue of noncompliance after the referral is made; although if all parties

agree, the timeframe can be extended.

- If the Joint Commission does not resolve the

compliance issue, any state can elevate the complaint to the ministers of

foreign affairs. The ministers then have 15 days (or longer by consensus)

to resolve the concern.

At the request of the state raising the noncompliance issue, or at the request of the state allegedly not in compliance, a three-member Advisory Board can be convened in parallel to the ministerial consideration or instead of ministerial consideration. The state that raised the issue of noncompliance and the accused state each appoint a member and the third is independent. The Advisory Board has 15 days to offer an opinion, which is nonbinding.

- The Joint Commission has five days to consider

the Advisory Board’s opinion.

- If the Joint Commission still has not resolved

the dispute and the complaining state believes it to “constitute

significant non-performance” of JCPOA commitments, the complaining state

could notify the Security Council. The notification must include a

description of efforts to resolve the issue.

- The Security Council then has 30 days to vote on

a resolution to continue lifting UN sanctions as outlined in Resolution

2231, which endorsed the deal and negated prior resolutions on Iran’s

nuclear activities. If such a resolution fails to pass, prior

Security Council resolutions on Iran will snap back into place (unless

the Security Council decides otherwise). The

sanctions would not apply retroactively.

U.S. Ambassador to the International

Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Jackie Wolcott called for an

emergency meeting of

the agency’s Board of Governors to discuss Iran’s nuclear activities. In the

July 5 statement announcing the U.S. request, Wolcott noted that it is

“essential for the Board to exercise its authority to accurately assess Iran’s

implementation of its safeguards obligations and nuclear commitments” and “hold

Iran’s regime accountable.” The IAEA announced it will hold the meeting July 10.

US representative to the

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Jackie Wolcott at a meeting of IAEA

Board of Governors in Vienna, November 22, 2018. (Photo:JOE KLAMAR /AFP/Getty

Images)

The IAEA Board of Governors,

comprised of representatives from 35 member states, approves safeguards

agreements and can refer a state to the Security Council if that state is not

in compliance with its IAEA safeguards obligations. The IAEA Board referred Iran to the Security

Council in 2006 after

Tehran failed to comply with the agency’s investigations into undeclared

nuclear activities. The IAEA Board does not, however, have the authority to

determine if Iran is violating the JCPOA. The reported breach of the JCPOA’s

300-kilogram limit, while concerning, is not an IAEA safeguards violation.

The United States may be requesting

an IAEA Board meeting to try build support to refer Iran’s nuclear file back to

the UN Security Council, circumventing the JCPOA’s dispute resolution process

for taking an issue to the UN.

Having withdrawn from the JCPOA,

Washington is no longer a member of the Joint Commission, which is the body set

up by the JCPOA to oversee implementation and is most likely to try and address

Iran’s breach of JCPOA restrictions or obligations. If the United States tries

to trigger the snapback mechanism in Resolution 2231 to reimpose Security

Council sanctions on Iran, it is likely that that other JCPOA parties will

challenge whether the United States has the legal standing to do so. The

provisions in the resolution only allow for participants in the JCPOA to

trigger sanctions snapback.

Senior Iranian officials reiterated

the threat that Tehran may withdraw from the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty

(NPT), ahead of the June 28 JCPOA Joint Commission meeting. According to

a June 27

report in The Wall Street Journal, an Iranian official told the Europeans that if the

nuclear deal falls apart, Iran may follow the path of North Korea and leave the

NPT.

Article X of the NPT allows states to

withdraw if “extraordinary events, related

Iran's Atomic Energy

Organisation spokesman Behrouz Kamalvandi and government spokesman Ali Rabiei

giving a joint press conferencd in Tehran, July 7, 2019. (Photo: Iranian

Presidency/AFP/Getty Images)

to the subject matter of this Treaty,

have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country.” A state must then give

three months’ notice to the Security Council explaining the rationale for its

withdrawal before the process is complete.

Iran has threatened in the past to

withdraw from the NPT. In April, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif stated that NPT withdrawal is one of the options Iran

is considering to respond to the U.S. pressure campaign. Iran also hinted at

withdrawal during the May 2019 NPT Preparatory Committee meeting for the

treaty’s 2020 Review Conference. During the meeting, Iran said that U.S. pressures to “dismantle the JCPOA” are

“detrimental not only to the stability and security in the Middle East region,

but to the NPT.” Iran will “adopt appropriate measures to preserve its supreme

national interests,” the statement said.

Iranian officials calling for NPT

withdrawal may believe that such a threat will increase leverage in

negotiations with the remaining P4+1 parties to the JCPOA on sanctions relief,

but taking such a drastic step would likely be interpreted as signaling

Tehran’s intention to pursue nuclear weapons, and increase Iran’s international

isolation on the issue.

The June 27 reference to

following North Korea’s path reinforces the perception that if Iran withdraws

from the NPT, it may choose to pursue nuclear weapons. North Korea first

initiated the withdrawal from the NPT in 1993 but suspended the action for a

decade before saying it completed the process in 2003. North Korea was

conducting illicit nuclear activities at the time of its attempted withdrawal

and later conducted its first nuclear weapon test explosion in 2006. North Korea

now possesses an arsenal of an estimated 20-30 nuclear weapons and

nuclear-capable ballistic missiles.

After a June 28 meeting of the Joint

Commission, the body set up by the nuclear deal to oversee implementation,

Secretary General of the European External Action Services Helga Schmid announced

in the chair’s

statement that

the first INSTEX transactions are being processed. INSTEX is a financial

mechanism set by France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, to provide a

financial channel for facilitating trade with Iran that bypasses U.S.

sanctions.

Schmid, who chaired the Joint

Commission meeting, also said additional EU member states were in the process

of joining INSTEX and cooperation with Iran on the mechanism “will speed up.”

Following the Joint Commission meeting, seven EU

states released a statement expressing support for the JCPOA and their

interest in participating in INSTEX, as did China.

While progress on INSTEX is positive,

it was unsurprising that these steps were not enough to head Iran off from

pursuing additional steps to violate the JCPOA July 7. Iranian Foreign Ministry

spokesperson Abbas Mousavi said the meeting was the “last chance” for the

P4+1 to “see how they can meet their commitments towards Iran.” He said if INSTEX is an “artificial mechanism,” Iran

will not accept it. Iran is looking for a route to sell oil, which INSTEX appears

unable to facilitate at this time.

The Joint Commission also discussed

the nuclear-related commitments during the June 28 meeting in Vienna. The

statement said participants “noted good progress” on the Arak reactor

conversion project and work at Fordow to establish a research and development

center and said that the parties “fully support these nuclear projects” and

their “timely completion.”

The United States issued waivers allowing nuclear cooperation on Arak and Fordow

to continue without the threat of sanctions violations, but the Trump

administration cut the waivers from the 180 days allowed to 90 and said they may

be revoked. This raised concerns that progress on these important nuclear

cooperation projects required by the JCPOA would slow. Iranian President Hassan

Rouhani said July 3 that Iran will resume work on the Arak reactor based on its

original design (which would produce enough plutonium for about two bombs per

year) if the P4+1 fail to meet their commitments to modify the reactor.

The Joint Commission also agreed to

have experts look into “practical solutions” for the export of low-enriched

uranium and heavy water. The deal allows Iran to sell low-enriched uranium and

heavy water to remain below the caps set by the deal but does not require the

P4+1 to facilitate or ensure any sales. The Trump administration refused to

renew waivers allowing Iran to sell or transfer low-enriched uranium and heavy

water in May, creating this issue.

The UN Secretary-General issued his

biannual report on the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2231,

which endorsed the nuclear deal and set restrictions on Iran’s ballistic

missile and conventional arms imports and exports.

The June 13 report noted that the Secretariat continued its

investigations into several transfers of conventional arms and ballistic

missiles from Iran, including systems that the Houthis fired into Saudi Arabia.

In several cases, the report concluded that the conventional arms and ballistic

missiles were of Iranian origin but could not determine if they were

transferred before or after January 2016, when Resolution 2231 came into

effect.

In the report, Secretary-General

Antonio Guterres expressed his “regret” for the U.S. decision not to renew

waivers for nuclear cooperation projects allowed under the JCPOA. He said the

U.S. decision “may also impede” Iran’s ability to meet its commitments under

the deal and said the actions are “contrary to goals” of the JCPOA and

Resolution 2231.

The report also contained an update

on the procurement channel, the mechanism set up by the JCPOA through which the

Security Council approves any transfer of dual-use materials and technologies

to Iran, against U.S. sanctions. Since the prior report in December, two

proposals were sent to the procurement channel and the Guterres said that he

received no new reports of illicit transfers of dual-use materials in violation

of the procurement channel. He also noted that two investigations into alleged

illicit transfers of dual-use technologies determined that the actions did not

violate Resolution 2231.

He also noted that the Russians have

proposed looking into options to secure the procurement channel against any

hindrance from U.S. sanctions targeting nuclear activities endorsed by

Resolution 2231 but did not mention any specific steps being undertaken at this

time. Guterres also expressed his support for efforts by the P4+1 to “to

protect the freedom of their economic operators to pursue legitimate business”

with Iran.

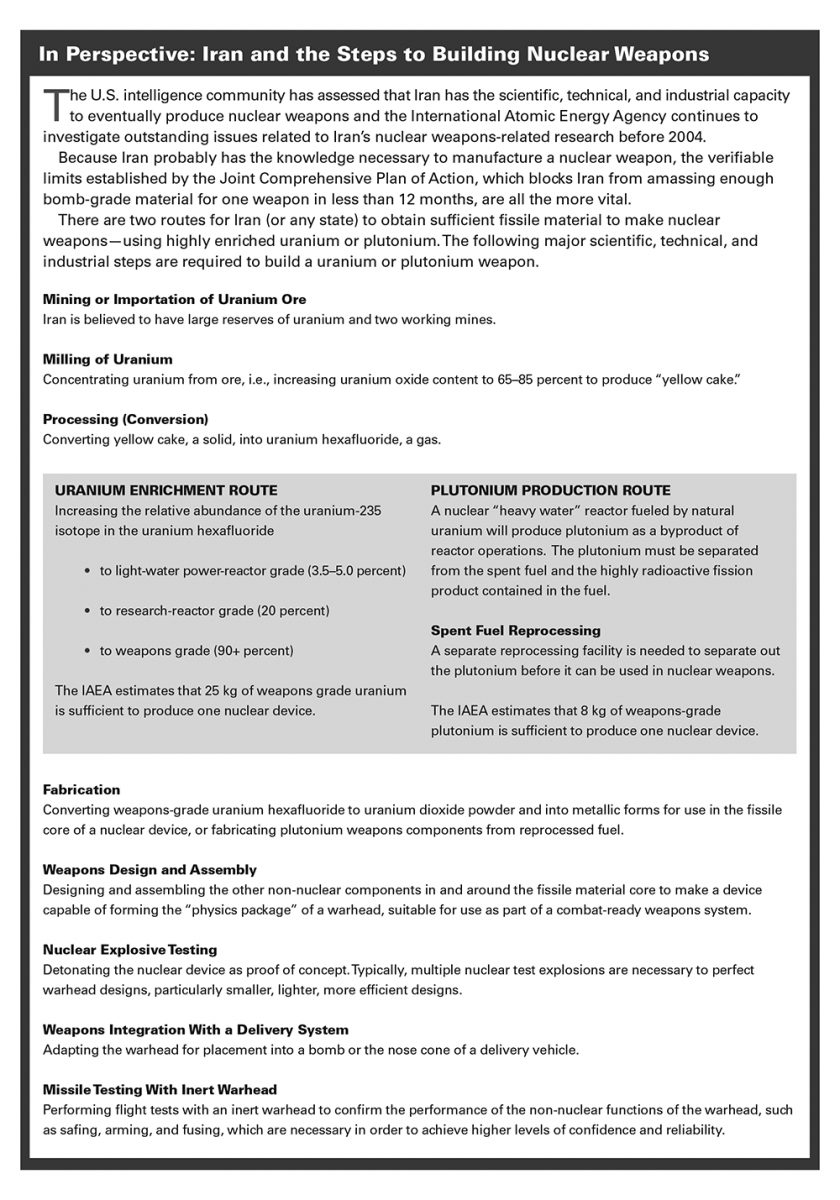

In Perspective: Iran and the Steps to Building Nuclear Weapons

Click to Download

The U.S. intelligence community has assessed that Iran has the scientific, technical, and industrial capacity to eventually produce nuclear weapons and the International Atomic Energy Agency continues to investigate outstanding issues related to Iran’s nuclear weapons-related research before 2004.

Because Iran probably has the knowledge necessary to manufacture a nuclear weapon, the verifiable limits established by the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which blocks Iran from amassing enough bomb-grade material for one weapon in less than 12 months, are all the more vital.

There are two routes for Iran (or any state) to obtain sufficient fissile material to make nuclear weapons—using highly enriched uranium or plutonium. This issue's Fact File details the major scientific, technical, and industrial steps required to build a uranium or plutonium weapon.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.