What the Next 18 Months Can

Look Like, if Leaders Buy Us Time

Coronavirus from SARS isolated in FRhK-4 cells. Thin section electron micrograph and negative stained virus particles

If you are an expert in the

field and want to criticize or endorse the article or some of its parts, feel

free to leave a private note here or contextually and I will respond or

address.

If you want to translate

this article, do it on a Medium post and leave me a private note here with your

link. Here are the translations currently available:

Spanish

(verified by author, full translation inc. charts)(alt. vs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

French (translated by an epidemiologist)

Chinese Traditional (full

translation including charts, alternative

translation)

Chinese

Simplified

German

Portuguese (alternative

version)

Russian

Italian

(with graphs translated)(Alternative

1, Alternative

version on Facebook)

Japanese

Vietnamese

Turkish

Polish

Icelandic (alternative

translation)

Greek

Bahasa

Indonesia

Bahasa

Malaysia

Farsi (alternative version outside of

Medium)

Czech (alternative

translation)

Dutch

Norwegian

Hebrew

Ukrainian (alternative

version)

Swedish

Romanian (alternative

version)

Bulgarian

Catalonian

Slovak

Filipino

Hungarian (Alternative, with part 1, part 2)

Summary of the article:

Strong coronavirus measures today should only last a few weeks, there shouldn’t

be a big peak of infections afterwards, and it can all be done for a reasonable

cost to society, saving millions of lives along the way. If we don’t take these

measures, tens of millions will be infected, many will die, along with anybody

else that requires intensive care, because the healthcare system will have

collapsed.

Within a week, countries

around the world have gone from: “This coronavirus thing is not a big deal”

to declaring the state of emergency. Yet many countries are still not doing

much. Why?

Every country is asking the

same question: How should we respond? The answer is not obvious to them.

Some countries, like France,

Spain or Philippines, have since ordered heavy lockdowns. Others, like the US,

UK, or Switzerland, have dragged their feet, hesitantly venturing into social

distancing measures.

Here’s what we’re going to

cover today, again with lots of charts, data and models with plenty of sources:

- What’s

the current situation?

- What options do we have?

- What’s the one thing that matters now: Time

- What does a good coronavirus strategy look like?

- How should we think about the economic and social

impacts?

When you’re done reading the

article, this is what you’ll take away:

Our healthcare system is

already collapsing.

Countries have two options: either they fight it hard now, or they will suffer

a massive epidemic.

If they choose the epidemic, hundreds of thousands will die. In some countries,

millions.

And that might not even eliminate further waves of infections.

If we fight hard now, we will curb the deaths.

We will relieve our healthcare system.

We will prepare better.

We will learn.

The world has never learned as fast about anything, ever.

And we need it, because we know so little about this virus.

All of this will achieve something critical: Buy Us Time.

If we choose to fight hard,

the fight will be sudden, then gradual.

We will be locked in for weeks, not months.

Then, we will get more and more freedoms back.

It might not be back to normal immediately.

But it will be close, and eventually back to normal.

And we can do all that while considering the rest of the economy too.

Ok, let’s do this.

1. What’s the situation?

Last week, I showed this

curve:

It showed coronavirus cases

across the world outside of China. We could only discern Italy, Iran and South

Korea. So I had to zoom in on the bottom right corner to see the emerging

countries. My entire point is that they would soon be joining these 3 cases.

Let’s see what has happened

since.

As predicted, the number of

cases has exploded in dozens of countries. Here, I was forced to show only

countries with over 1,000 cases. A few things to note:

- Spain, Germany, France and the US all have more

cases than Italy when it ordered the lockdown

- An additional 16 countries have more cases today

than Hubei when it went under lockdown: Japan, Malaysia, Canada, Portugal,

Australia, Czechia, Brazil and Qatar have more than Hubei but below 1,000

cases. Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Austria, Belgium, Netherlands and

Denmark all have above 1,000 cases.

Do you notice something

weird about this list of countries? Outside of China and Iran, which have

suffered massive, undeniable outbreaks, and Brazil and Malaysia, every single

country in this list is among the wealthiest in the world.

Do you think this virus

targets rich countries? Or is it more likely that rich countries are better

able to identify the virus?

It’s unlikely that poorer

countries aren’t touched. Warm and humid weather probably helps, but doesn’t prevent an outbreak by itself —

otherwise Singapore, Malaysia or Brazil wouldn’t be suffering outbreaks.

The most likely

interpretations are that the coronavirus either took longer to reach these

countries because they’re less connected, or it’s already there but these

countries haven’t been able to invest enough on testing to know.

Either way, if this is true,

it means that most countries won’t escape the coronavirus. It’s a matter of

time before they see outbreaks and need to take measures.

What measures can different

countries take?

2. What Are Our Options?

Since the article last week,

the conversation has changed and many countries have taken measures. Here are

some of the most illustrative examples:

Measures in Spain and France

In one extreme, we have

Spain and France. This is the timeline of measures for Spain:

On Thursday, 3/12, the

President dismissed suggestions that the Spanish authorities had been

underestimating the health threat.

On Friday, they declared the State of Emergency.

On Saturday, measures were taken:

- People can’t leave home except for key reasons:

groceries, work, pharmacy, hospital, bank or insurance company (extreme

justification)

- Specific ban on taking kids out for a walk or

seeing friends or family (except to take care of people who need help, but

with hygiene and physical distance measures)

- All bars and restaurants closed. Only

take-home acceptable.

- All entertainment closed: sports, movies,

museums, municipal celebrations…

- Weddings can’t have guests. Funerals can’t have

more than a handful of people.

- Mass

transit remains open

On Monday, land borders were

shut.

Some people see this as a

great list of measures. Others put their hands up in the air and cry of

despair. This difference is what this article will try to reconcile.

France’s timeline of

measures is similar, except they took more time to apply them, and they are

more aggressive now. For example, rent, taxes and utilities are suspended for

small businesses.

Measures in the US and UK

The US and UK, like

countries such as Switzerland, have dragged their feet in implementing

measures. Here’s the timeline for the US:

- Wednesday

3/11: travel ban.

- Friday: National Emergency declared. No social

distancing measures

- Monday: the government urges the public to avoid

restaurants or bars and attend events with more than 10 people. No social

distancing measure is actually enforceable. It’s just a suggestion.

Lots of states and cities

are taking the initiative and mandating much stricter measures.

The UK has seen a similar

set of measures: lots of recommendations, but very few mandates.

These two groups of

countries illustrate the two extreme approaches to fight the coronavirus:

mitigation and suppression. Let’s understand what they mean.

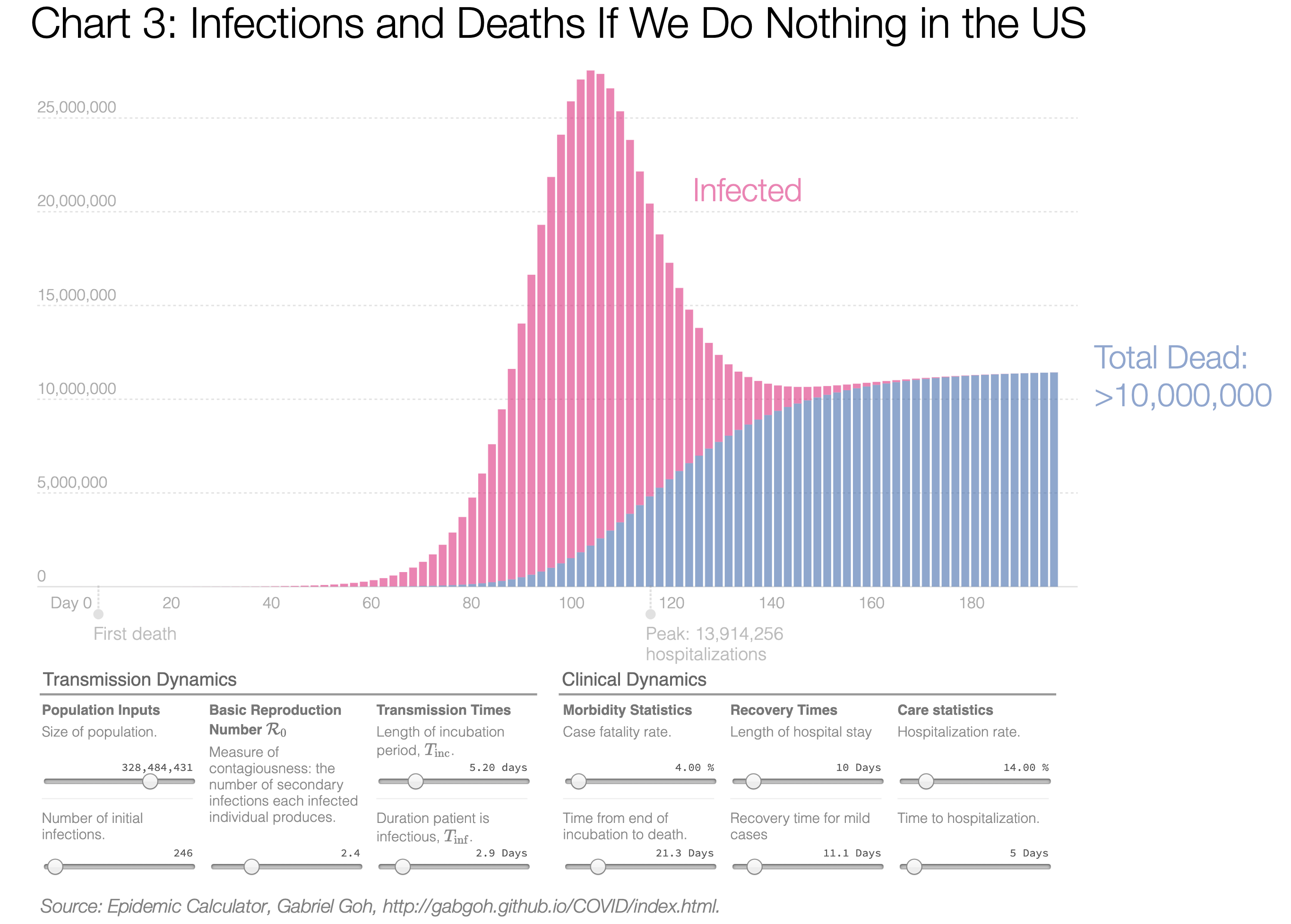

Option 1: Do Nothing

Before we do that, let’s see

what doing nothing would entail for a country like the US:

This fantastic epidemic calculator can help you understand what will happen under

different scenarios. I’ve pasted below the graph the key factors that determine

the behavior of the virus. Note that infected, in pink, peak in the tens of

millions at a certain date. Most variables have been kept from the default. The

only material changes are R from 2.2 to 2.4 (corresponds better to currently

available information. See at the bottom of the epidemic calculator), fatality

rate (4% due to healthcare system collapse. See details below or in the previous

article),

length of hospital stay (down from 20 to 10 days) and hospitalization rate

(down from 20% to 14% based on severe and critical cases. Note the WHO calls

out a 20% rate) based on our most recently available gathering

of research.

Note that these numbers don’t change results much. The only change that matters

is the fatality rate.

If we do nothing: Everybody

gets infected, the healthcare system gets overwhelmed, the mortality explodes,

and ~10 million people die (blue bars). For the back-of-the-envelope numbers:

if ~75% of Americans get infected and 4% die, that’s 10 million deaths, or

around 25 times the number of US deaths in

World War II.

You might wonder: “That

sounds like a lot. I’ve heard much less than that!”

So what’s the catch? With

all these numbers, it’s easy to get confused. But there’s only two numbers that

matter: What share of people will catch the virus and fall sick, and what share

of them will die. If only 25% are sick (because the others have the virus but

don’t have symptoms so aren’t counted as cases), and the fatality rate is 0.6%

instead of 4%, you end up with 500k deaths in the US.

If we don’t do anything, the

number of deaths from the coronavirus will probably land between these two

numbers. The chasm between these extremes is mostly driven by the fatality

rate, so understanding it better is crucial. What really causes the coronavirus

deaths?

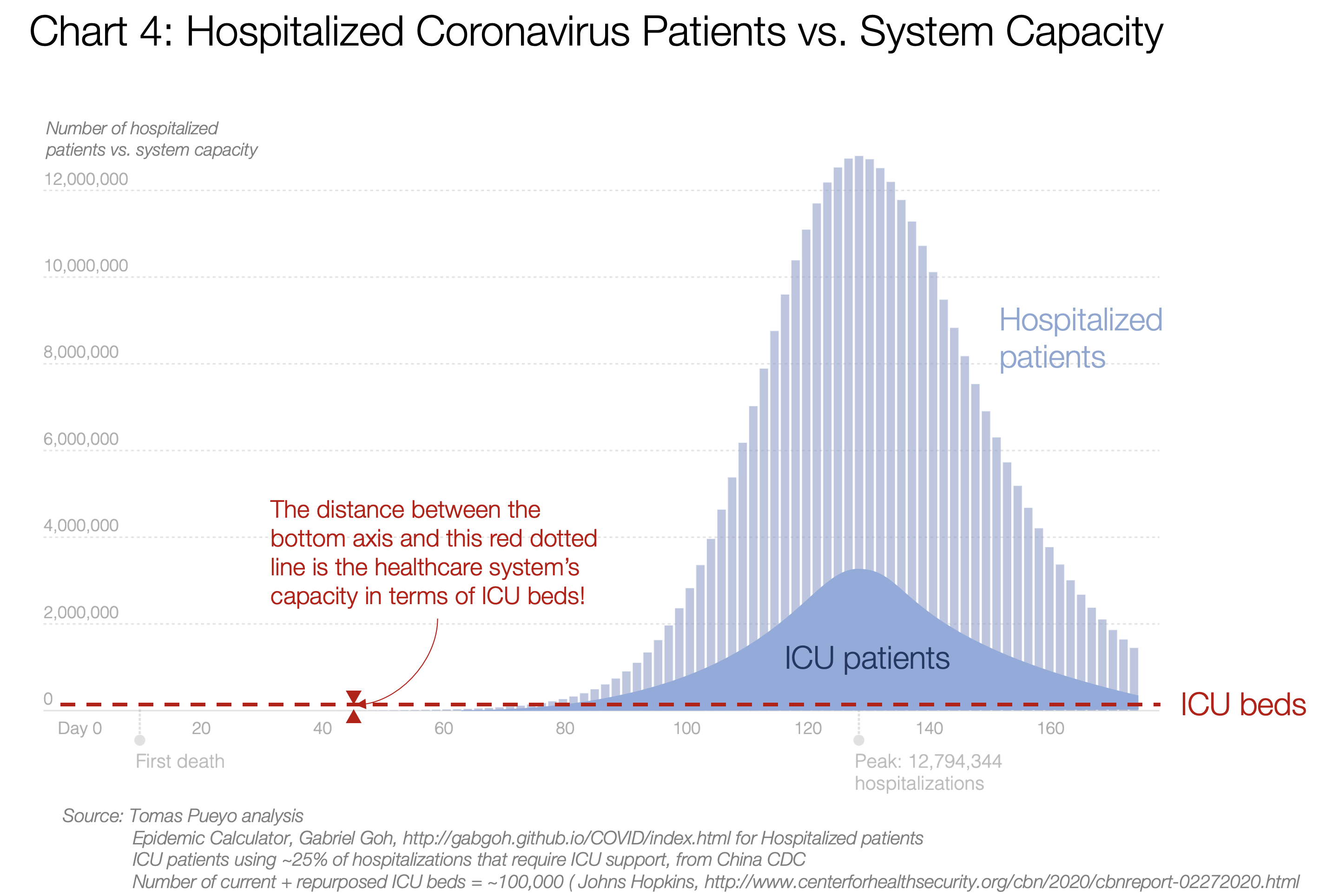

How Should We Think about

the Fatality Rate?

This is the same graph as

before, but now looking at hospitalized people instead of infected and dead:

The light blue area is the

number of people who would need to go to the hospital, and the darker blue

represents those who need to go to the intensive care unit (ICU). You can see

that number would peak at above 3 million.

Now compare that to the

number of ICU beds we have in the US (50k today, we could double that

repurposing other space). That’s the red dotted line.

No, that’s not an error.

That red dotted line is the

capacity we have of ICU beds. Everyone above that line would be in critical

condition but wouldn’t be able to access the care they need, and would likely

die.

This is why people died in

droves in Hubei and are now dying in droves in Italy and Iran. The Hubei

fatality rate ended up better than it could have been because they built 2

hospitals nearly overnight. Italy and Iran can’t do the same; few, if any,

other countries can. We’ll see what ends up happening there.

So why is the fatality rate

close to 4%?

If 5% of your cases require

intensive care and you can’t provide it, most of those people die. As simple as

that.

I wish that was all, but it

isn’t.

Collateral Damage

These numbers only show

people dying from coronavirus. But what happens if all your healthcare system

is collapsed by coronavirus patients? Others also die from other ailments.

What happens if you have a

heart attack but the ambulance takes 50 minutes to come instead of 8 (too many

coronavirus cases) and once you arrive, there’s no ICU and no doctor available?

You die.

There are 4 million admissions to the ICU in the US every year, and 500k (~13%) of them

die. Without ICU beds, that share would likely go much closer to 80%. Even if

only 50% died, in a year-long epidemic you go from 500k deaths a year to 2M, so

you’re adding 1.5M deaths, just with collateral damage.

If the coronavirus is left

to spread, the US healthcare system will collapse, and the deaths will be in

the millions, maybe more than 10 million.

The same thinking is true

for most countries. The number of ICU beds and ventilators and healthcare

workers are usually similar to the US or lower in most countries. Unbridled

coronavirus means healthcare system collapse, and that means mass death.

Unbridled coronavirus means

healthcare systems collapse, and that means mass death.

By now, I hope it’s pretty

clear we should act. The two options that we have are mitigation and

suppression. Both of them propose to “flatten the curve”, but they go about it

very differently.

Option 2: Mitigation

Strategy

Mitigation goes like this: “It’s

impossible to prevent the coronavirus now, so let’s just have it run its

course, while trying to reduce the peak of infections. Let’s just flatten the

curve a little bit to make it more manageable for the healthcare system.”

This chart appears in a very

important paper published over the weekend from the Imperial

College London. Apparently, it pushed the UK and US governments to change

course.

It’s a very similar graph as

the previous one. Not the same, but conceptually equivalent. Here, the “Do

Nothing” situation is the black curve. Each one of the other curves are what

would happen if we implemented tougher and tougher social distancing measures.

The blue one shows the toughest social distancing measures: isolating infected

people, quarantining people who might be infected, and secluding old people.

This blue line is broadly the current UK

coronavirus strategy,

although for now they’re just suggesting it, not mandating it.

Here, again, the red line is

the capacity for ICUs, this time in the UK. Again, that line is very close to

the bottom. All that area of the curve on top of that red line represents

coronavirus patients who would mostly die because of the lack of ICU resources.

Not only that, but by

flattening the curve, the ICUs will collapse for months, increasing collateral

damage.

You should be shocked. When

you hear: “We’re going to do some mitigation” what they’re really saying

is: “We will knowingly overwhelm the healthcare system, driving the fatality

rate up by a factor of 10x at least.”

You would imagine this is

bad enough. But we’re not done yet. Because one of the key assumptions of this

strategy is what’s called “Herd Immunity”.

Herd Immunity and Virus

Mutation

The idea is that all the

people who are infected and then recover are now immune to the virus. This is

at the core of this strategy: “Look, I know it’s going to be hard for some

time, but once we’re done and a few million people die, the rest of us will be

immune to it, so this virus will stop spreading and we’ll say goodbye to the

coronavirus. Better do it at once and be done with it, because our alternative

is to do social distancing for up to a year and risk having this peak happen

later anyways.”

Except this assumes one

thing: the virus doesn’t change too much. If it doesn’t change much, then lots

of people do get immunity, and at some point the epidemic dies down

How likely is this virus to

mutate?

It seems it already has.

This graph represents the

different mutations of the virus. You can see that the initial strains started in

purple in China and then spread. Each time you see a branching on the left

graph, that is a mutation leading to a slightly different variant of the virus.

This should not be

surprising: RNA-based viruses like the coronavirus or the flu tend to mutate around 100 times faster than DNA-based ones—although the coronavirus mutates more slowly than

influenza viruses.

Not only that, but the best

way for this virus to mutate is to have millions of opportunities to do so,

which is exactly what a mitigation strategy would provide: hundreds of millions

of people infected.

That’s why you have to get a

flu shot every year. Because there are so many flu strains, with new ones

always evolving, the flu shot can never protect against all strains.

Put in another way: the

mitigation strategy not only assumes millions of deaths for a country like the

US or the UK. It also gambles on the fact that the virus won’t mutate too much

— which we know it does. And it will give it the opportunity to mutate. So once

we’re done with a few million deaths, we could be ready for a few million more

— every year. This corona virus could become a recurring fact of

life, like the flu, but many times deadlier.

The best way for this virus

to mutate is to have millions of opportunities to do so, which is exactly what

a mitigation strategy would provide.

So if neither doing nothing

and mitigation will work, what’s the alternative? It’s called suppression.

Option 3: Suppression Strategy

The Mitigation Strategy

doesn’t try to contain the epidemic, just flatten the curve a bit. Meanwhile,

the Suppression Strategy tries to apply heavy measures to quickly get the

epidemic under control. Specifically:

- Go hard right now. Order heavy social distancing.

Get this thing under control.

- Then, release the measures, so that people can

gradually get back their freedoms and something approaching normal social

and economic life can resume.

What does that look like?

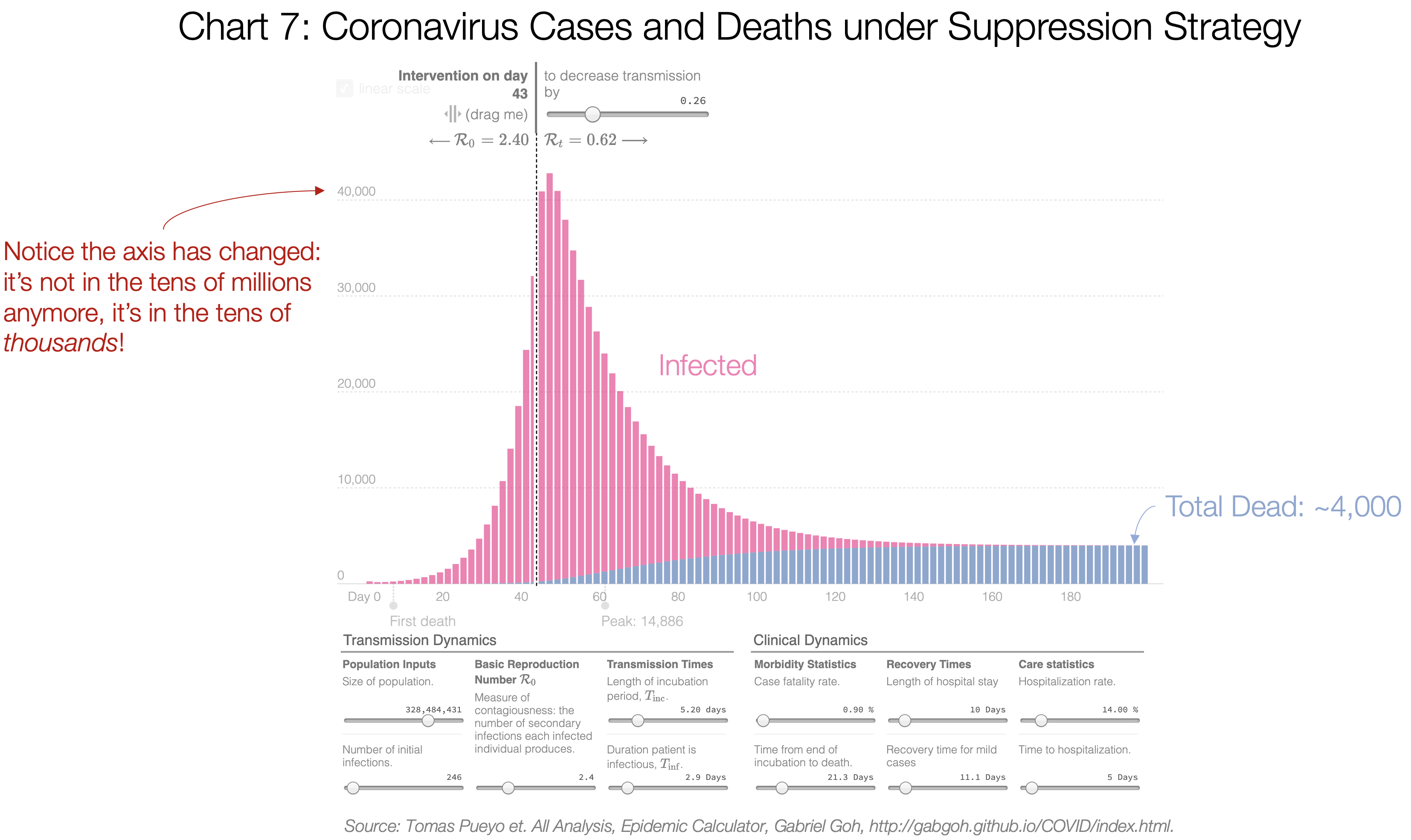

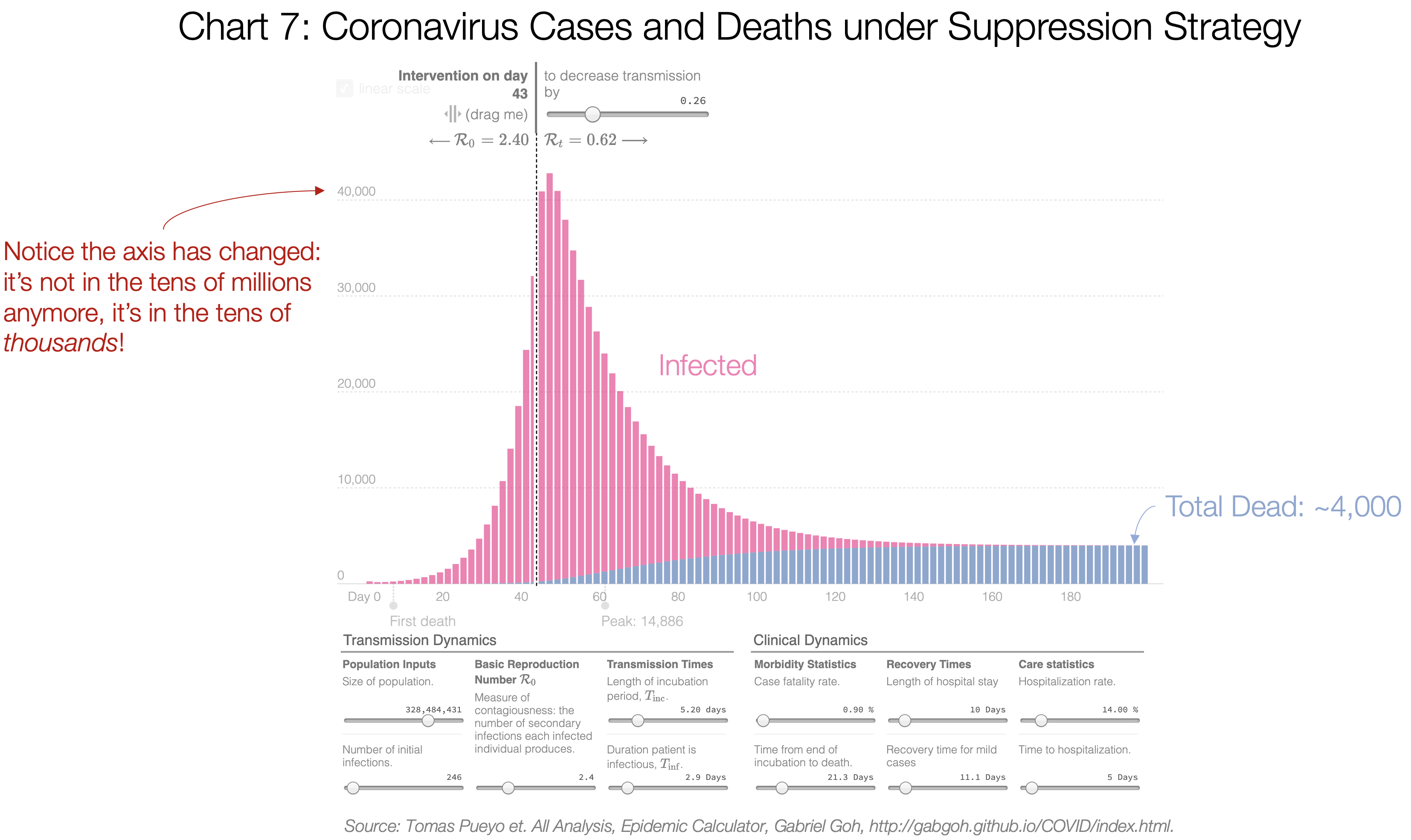

All the model parameters are

the same, except that there is an intervention around now to reduce the

transmission rate to R=0.62, and because the healthcare system isn’t collapsed,

the fatality rate goes down to 0.6%. I defined “around now” as having ~32,000

cases when implementing the measures (3x the official number as of today,

3/19). Note that this is not too sensitive to the R chosen. An R of 0.98 for

example shows 15,000 deaths. Five times more than with an R of 0.62, but still

tens of thousands of deaths and not millions. It’s also not too sensitive to

the fatality rate: if it’s 0.7% instead of 0.6%, the death toll goes from

15,000 to 17,000. It’s the combination of a higher R, a higher fatality rate,

and a delay in taking measures that explodes the number of fatalities. That’s

why we need to take measures to reduce R today. For clarification, the famous

R0 is R at the beginning (R at time 0). It’s the transmission rate when nobody

is immune yet and there are no measures against it taken. R is the overall

transmission rate.

Under a suppression

strategy, after the first wave is done, the death toll is in the thousands, and

not in the millions.

Why? Because not only do we

cut the exponential growth of cases. We also cut the fatality rate since the

healthcare system is not completely overwhelmed. Here, I used a fatality rate

of 0.9%, around what we’re seeing in South Korea today, which has been most

effective at following Suppression Strategy.

Said like this, it sounds

like a no-brainer. Everybody should follow the Suppression Strategy.

So why do some governments

hesitate?

They

fear three things:

- This first lockdown will last for months, which

seems unacceptable for many people.

- A months-long lockdown would destroy the economy.

- It wouldn’t even solve the problem, because we

would be just postponing the epidemic: later on, once we release the

social distancing measures, people will still get infected in the millions

and die.

Here is how the Imperial

College team modeled suppressions. The green and yellow lines are different

scenarios of Suppression. You can see that doesn’t look good: We still get huge

peaks, so why bother?

We’ll get to these questions

in a moment, but there’s something more important before.

This is completely missing

the point.

Presented like these, the

two options of Mitigation and Suppression, side by side, don’t look very

appealing. Either a lot of people die soon and we don’t hurt the economy today,

or we hurt the economy today, just to postpone the deaths.

This ignores the value of

time.

3. The Value of Time

In our previous post, we

explained the value of time in saving lives. Every day, every hour we waited to

take measures, this exponential threat continued spreading. We saw how a single day could reduce the total cases by

40% and the death toll by even more.

But time is even more

valuable than that.

We’re about to face the

biggest wave of pressure on the healthcare system ever seen in history. We are

completely unprepared, facing an enemy we don’t know. That is not a good

position for war.

What if you were about to

face your worst enemy, of which you knew very little, and you had two options:

Either you run towards it, or you escape to buy yourself a bit of time to

prepare. Which one would you choose?

This is what we need to do

today. The world has awakened. Every single day we delay the coronavirus, we

can get better prepared. The next sections detail what that time would buy us:

Lower the Number of Cases

With effective suppression,

the number of true cases would plummet overnight, as we saw in

Hubei last week.

As of today, there are 0

daily new cases of coronavirus in the entire 60 million-big region of Hubei.

The diagnostics would keep

going up for a couple of weeks, but then they would start going down. With

fewer cases, the fatality rate starts dropping too. And the collateral damage

is also reduced: fewer people would die from non-coronavirus-related causes

because the healthcare system is simply overwhelmed.

Suppression

would get us:

- Fewer

total cases of Coronavirus

- Immediate relief for the healthcare system and

the humans who run it

- Reduction

in fatality rate

- Reduction

in collateral damage

- Ability for infected, isolated and quarantined

healthcare workers to get better and back to work. In

Italy, healthcare workers represent 8% of all contagions.

Understand the True Problem:

Testing and Tracing

Right now, the UK and the US

have no idea about their true cases. We don’t know how many there are. We just

know the official number is not right, and the true one is in the tens of

thousands of cases. This has happened because we’re not testing, and we’re not

tracing.

- With a few more weeks, we could get our testing

situation in order, and start testing everybody. With that

information, we would finally know the true extent of the problem, where

we need to be more aggressive, and what communities are safe to be released

from a lockdown.

- New testing methods could speed up testing and drive costs down substantially.

- We could also set up a tracing operation like the

ones they have in China or other East Asia countries, where they can

identify all the people that every sick person met, and can put them in

quarantine. This would give us a ton of intelligence to release later on

our social distancing measures: if we know where the

virus is, we can target these places only. This is not rocket science:

it’s the basics of how East Asia Countries have been able to control this

outbreak without the kind of draconian social distancing that is

increasingly essential in other countries.

The measures from this

section (testing and tracing) single-handedly curbed the growth of the

coronavirus in South Korea and got the epidemic under control, without a strong

imposition of social distancing measures.

Build Up Capacity

The US (and presumably the

UK) are about to go to war without armor.

We have masks for just

two weeks, few

personal protective equipments (“PPE”), not enough ventilators, not enough ICU

beds, not enough ECMOs (blood oxygenation machines)… This is why the fatality

rate would be so high in a mitigation strategy.

But if we buy ourselves some

time, we can turn this around:

- We have more time to buy equipment we will need

for a future wave

- We can quickly build up our production of masks,

PPEs, ventilators, ECMOs, and any other critical device to reduce

fatality rate.

Put in another way: we don’t

need years to get our armor, we need weeks. Let’s do everything we can to get

our production humming now. Countries are mobilized. People are being

inventive, such as using 3D

printing for ventilator parts. We can do it. We just need more time. Would you wait

a few weeks to get yourself some armor before facing a mortal enemy?

This is not the only

capacity we need. We will need health workers as soon as possible. Where will

we get them? We need to train people to assist nurses, and we need to get

medical workers out of retirement. Many countries have already started, but

this takes time. We can do this in a few weeks, but not if everything

collapses.

Lower Public Contagiousness

The public is scared. The

coronavirus is new. There’s so much we don’t know how to do yet! People haven’t

learned to stop hand-shaking. They still hug. They don’t open doors with their

elbow. They don’t wash their hands after touching a door knob. They don’t

disinfect tables before sitting.

Once we have enough masks,

we can use them outside of the healthcare system too. Right now, it’s better to

keep them for healthcare workers. But if they weren’t scarce, people should wear

them in

their daily lives, making it less likely that they infect other people when

sick, and with proper training also reducing the likelihood that the wearers

get infected. (In the meantime, wearing

something is better than nothing.)

All of these are pretty

cheap ways to reduce the transmission rate. The less this virus propagates, the

fewer measures we’ll need in the future to contain it. But we need time to

educate people on all these measures and equip them.

Understand the Virus

We know very very little

about the virus. But every week, hundreds of new papers are coming.

The world is finally united

against a common enemy. Researchers around the globe are mobilizing to

understand this virus better.

How does the virus spread?

How can contagion be slowed down?

What is the share of asymptomatic carriers?

Are they contagious? How much?

What are good treatments?

How long does it survive?

On what surfaces?

How do different social distancing measures impact the transmission rate?

What’s their cost?

What are tracing best practices?

How reliable are our tests?

Clear answers to these

questions will help make our response as targeted as possible while minimizing

collateral economic and social damage. And they will come in weeks, not years.

Find Treatments

Not only that, but what if

we found a treatment in the next few weeks? Any day we buy gets us closer to

that. Right now, there are already several

candidates,

such as Favipiravir, Chloroquine, or Chloroquine

combined with Azithromycin. What if it turned out that in two months we discovered a treatment for

the coronavirus? How stupid would we look if we already had millions of deaths

following a mitigation strategy?

Understand the Cost-Benefits

All of the factors above can

help us save millions of lives. That should be enough. Unfortunately,

politicians can’t only think about the lives of the infected. They must think

about all the population, and heavy social distancing measures have an impact

on others.

Right now we have no idea

how different social distancing measures reduce transmission. We also have no

clue what their economic and social costs are.

Isn’t it a bit difficult to

decide what measures we need for the long term if we don’t know their cost or

benefit?

A few weeks would give us

enough time to start studying them, understand them, prioritize them, and

decide which ones to follow.

Fewer cases, more

understanding of the problem, building up assets, understanding the virus,

understanding the cost-benefit of different measures, educating the public…

These are some core tools to fight the virus, and we just need a few weeks to

develop many of them. Wouldn’t it be dumb to commit to a strategy that throws

us instead, unprepared, into the jaws of our enemy?

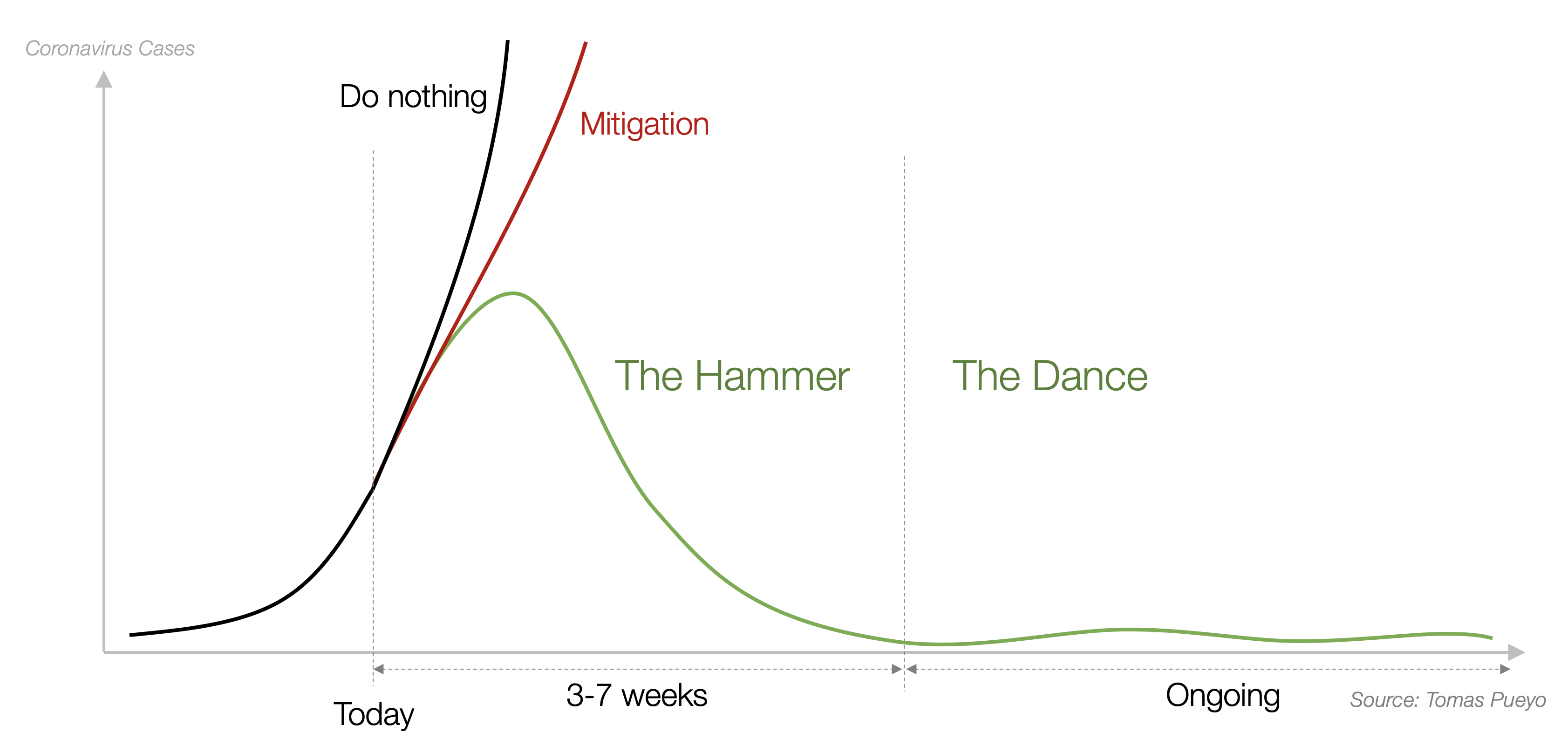

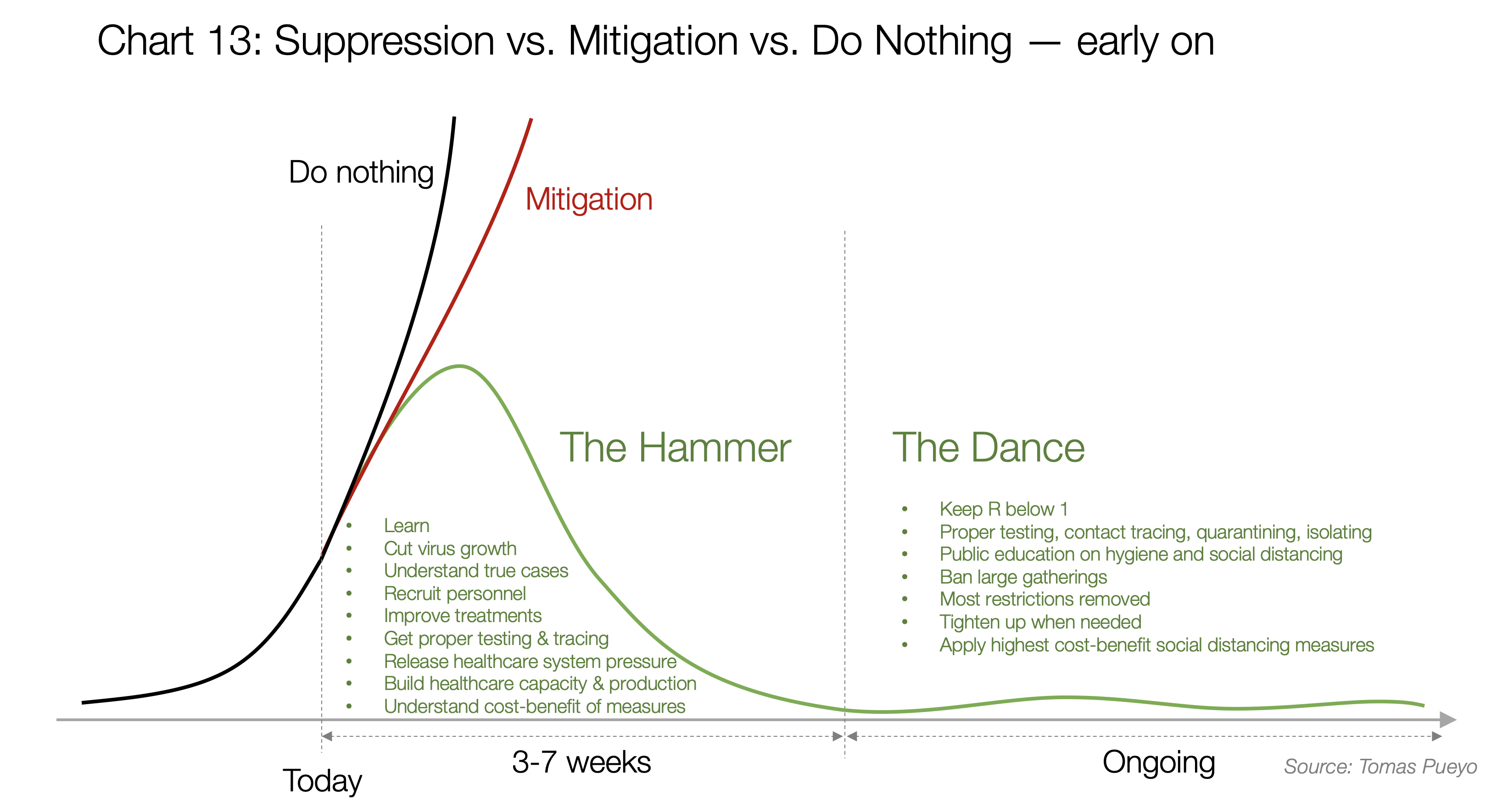

4. The Hammer and the Dance

Now we know that the

Mitigation Strategy is probably a terrible choice, and that the Suppression

Strategy has a massive short-term advantage.

But people have rightful

concerns about this strategy:

- How long will it actually last?

- How expensive will it be?

- Will there be a second peak as big as if we

didn’t do anything?

Here, we’re going to look at

what a true Suppression Strategy would look like. We can call it the Hammer and

the Dance.

The Hammer

First, you act quickly and

aggressively. For all the reasons we mentioned above, given the value of time,

we want to quench this thing as soon as possible.

One of the most important

questions is: How long will this last?

The fear that everybody has

is that we will be locked inside our homes for months at a time, with the

ensuing economic disaster and mental breakdowns. This idea was unfortunately

entertained in the famous Imperial College paper:

Do you remember this chart?

The light blue area that goes from end of March to end of

August is the period that the paper recommends as the Hammer, the initial

suppression that includes heavy social distancing.

If you’re a politician and

you see that one option is to let hundreds of thousands or millions of people

die with a mitigation strategy and the other is to stop the economy for five

months before going through the same peak of cases and deaths, these don’t

sound like compelling options.

But this doesn’t need to be

so. This paper, driving policy today, has been brutally

criticized for

core flaws: They ignore contact tracing (at the core of policies in South

Korea, China or Singapore among others) or travel restrictions (critical in

China), ignore the impact of big crowds…

The time needed for the

Hammer is weeks, not months.

This graph shows the new

cases in the entire Hubei region (60 million people) every day since 1/23.

Within 2 weeks, the country was starting to get back to work. Within ~5 weeks

it was completely under control. And within 7 weeks the new diagnostics was

just a trickle. Let’s remember this was the worst region in China.

Remember again that these

are the orange bars. The grey bars, the true cases, had plummeted much earlier

(see Chart 9).

The measures they took

were pretty similar to the ones taken in Italy, Spain or France:

isolations, quarantines, people had to stay at home unless there was an

emergency or had to buy food, contact tracing, testing, more hospital beds,

travel bans…

Details matter, however.

China’s measures were

stronger. For example, people were limited to one person per household allowed

to leave home every three days to buy food. Also, their enforcement was severe.

It is likely that this severity stopped the epidemic faster.

In Italy, France and Spain,

measures were not as drastic, and their implementation is not as tough. People

still walk on the streets, many without masks. This is likely to result in a

slower Hammer: more time to fully control the epidemic.

Some people interpret this

as “Democracies will never be able to replicate this reduction in cases”.

That’s

wrong.

For several weeks, South

Korea had the worst epidemic outside of China. Now, it’s largely under control.

And they did it without asking people to stay home. They achieved it mostly

with very aggressive testing, contact tracing, and enforced quarantines and

isolations.

The following table gives a

good sense of what measures different countries have followed, and how that has

impacted them (this is a work-in-progress. Feedback welcome.)

This shows how countries who

were prepared, with stronger epidemiological authority, education on hygiene

and social distancing, and early detection and isolation, didn’t have to pay

with heavier measures afterwards.

Conversely, countries like

Italy, Spain or France weren’t doing these well, and had to then apply the

Hammer with the hard measures at the bottom to catch up.

The lack of measures in the

US and UK is in stark contrast, especially in the US. These countries are still

not doing what allowed Singapore, South Korea or Taiwan to control the virus,

despite their outbreaks growing exponentially. But it’s a matter of time.

Either they have a massive epidemic, or they realize late their mistake, and

have to overcompensate with a heavier Hammer. There is no escape from this.

But it’s doable. If an

outbreak like South Korea’s can be controlled in weeks and without mandated

social distancing, Western countries, which are already applying a heavy Hammer

with strict social distancing measures, can definitely control the outbreak

within weeks. It’s a matter of discipline, execution, and how much the

population abides by the rules.

Once the Hammer is in place

and the outbreak is controlled, the second phase begins: the Dance.

The Dance

If you hammer the

coronavirus, within a few weeks you’ve controlled it and you’re in much better

shape to address it. Now comes the longer-term effort to keep this virus

contained until there’s a vaccine.

This is probably the single

biggest, most important mistake people make when thinking about this stage:

they think it will keep them home for months. This is not the case at all. In

fact, it is likely that our lives will go back to close to normal.

The Dance in Successful

Countries

How come South Korea,

Singapore, Taiwan and Japan have had cases for a long time, in the case of

South Korea thousands of them, and yet they’re not locked down home?

In this video, the South

Korea Foreign Minister explains how her country did it. It was pretty simple:

efficient testing, efficient tracing, travel bans, efficient isolating and

efficient quarantining.

This paper explains

Singapore’s approach:

Want to guess their

measures? The same ones as in South Korea. In their case, they complemented

with economic help to those in quarantine and travel bans and delays.

Is it too late for these

countries and others? No. By applying the Hammer, they’re getting a new chance,

a new shot at doing this right. The more they wait, the heavier and longer the

hammer, but it can control the epidemics.

But what if all these

measures aren’t enough?

The Dance of R

I call the months-long

period between the Hammer and a vaccine or effective treatment the Dance

because it won’t be a period during which measures are always the same harsh

ones. Some regions will see outbreaks again, others won’t for long periods of

time. Depending on how cases evolve, we will need to tighten up social

distancing measures or we will be able to release them. That is the dance of R:

a dance of measures between getting our lives back on track and spreading the

disease, one of economy vs. healthcare.

How does this dance work?

It all turns around the R.

If you remember, it’s the transmission rate. Early on in a standard, unprepared

country, it’s somewhere between 2 and 3: During the few weeks that somebody is

infected, they infect between 2 and 3 other people on average.

If R is above 1, infections

grow exponentially into an epidemic. If it’s below 1, they die down.

During the Hammer, the goal

is to get R as close to zero, as fast as possible, to quench the epidemic. In

Wuhan, it is

calculated that

R was initially 3.9, and after the lockdown and centralized quarantine, it went

down to 0.32.

But once you move into the

Dance, you don’t need to do that anymore. You just need your R to stay below 1:

a lot of the social distancing measures have true, hard costs on people. They

might lose their job, their business, their healthy habits…

You can remain below R=1

with a few simple measures.

This is an approximation of

how different types of patients respond to the virus, as well as their

contagiousness. Nobody knows the true shape of this curve, but we’ve gathered

data from different papers to approximate how it looks like.

Every day after they

contract the virus, people have some contagion potential. Together, all these

days of contagion add up to 2.5 contagions on average.

It is believed that there

are some contagions already happening during the “no symptoms” phase. After

that, as symptoms grow, usually people go to the doctor, get diagnosed, and

their contagiousness diminishes.

For example, early on you

have the virus but no symptoms, so you behave as normal. When you speak with

people, you spread the virus. When you touch your nose and then open door knob,

the next people to open the door and touch their nose get infected.

The more the virus is

growing inside you, the more infectious you are. Then, once you start having

symptoms, you might slowly stop going to work, stay in bed, wear a mask, or

start going to the doctor. The bigger the symptoms, the more you distance

yourself socially, reducing the spread of the virus.

Once you’re hospitalized,

even if you are very contagious you don’t tend to spread the virus as much

since you’re isolated.

This is where you can see

the massive impact of policies like those of Singapore or South Korea:

- If people are massively tested, they can be

identified even before they have symptoms. Quarantined,

they can’t spread anything.

- If people are trained to identify their symptoms

earlier, they reduce the number of days in blue, and hence their overall

contagiousness

- If people are isolated as soon as they have

symptoms, the contagions from the orange phase disappear.

- If people are educated about personal distance,

mask-wearing, washing hands or disinfecting spaces, they spread less virus

throughout the entire period.

Only when all these fail do

we need heavier social distancing measures.

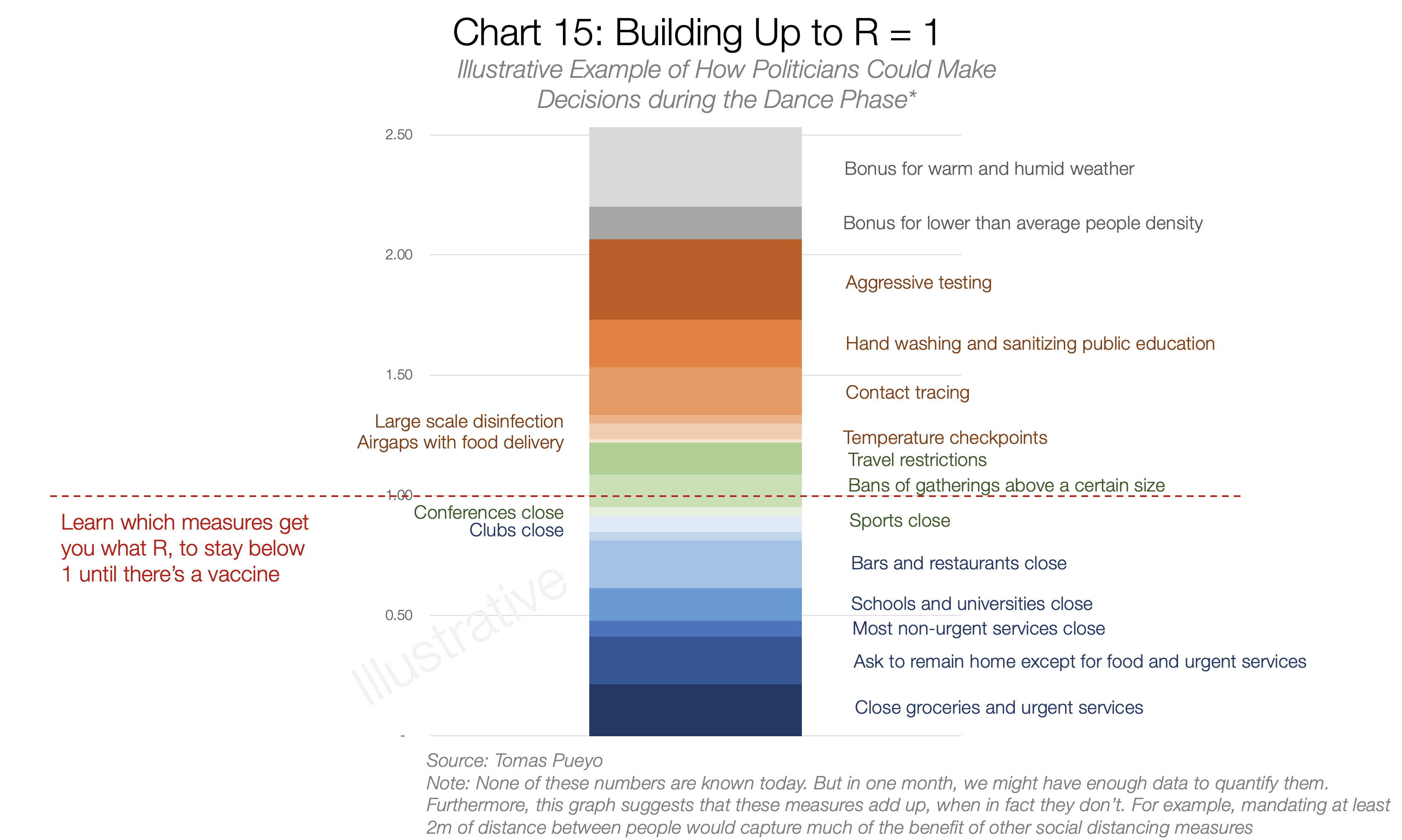

The ROI of Social Distancing

If with all these measures

we’re still way above R=1, we need to reduce the average number of people that

each person meets.

There are some very cheap

ways to do that, like banning events with more than a certain number of people

(eg, 50, 500), or asking people to work from home when they can.

Other are much, much more

expensive economically, socially and ethically, such as closing schools and

universities, asking everybody to stay home, or closing businesses.

This chart is made up

because it doesn’t exist today. Nobody has done enough research about this or

put together all these measures in a way that can compare them.

It’s unfortunate, because

it’s the single most important chart that politicians would need to make

decisions. It illustrates what is really going through their minds.

During the Hammer period,

politicians want to lower R as much as possible, through measures that remain

tolerable for the population. In Hubei, they went all the way to 0.32. We might

not need that: maybe just to 0.5 or 0.6.

But during the Dance of the

R period, they want to hover as close to 1 as possible, while staying below it

over the long term term. That prevents a new outbreak, while eliminating the

most drastic measures.

What this means is that,

whether leaders realize it or not, what they’re doing is:

- List all the measures they can take to reduce R

- Get a sense of the benefit of applying them: the

reduction in R

- Get a sense of their cost: the economic, social,

and ethical cost.

- Stack-rank the initiatives based on their

cost-benefit

- Pick the ones that give the biggest R reduction

up till 1, for the lowest cost.

This is for illustrative

purposes only. All data is made up. However, as far as we were able to tell,

this data doesn’t exist today. It needs to. For example, the list from the

CDC is a great

start, but it misses things like education measures, triggers, quantifications

of costs and benefits, measure details, economic / social countermeasures…

Initially, their confidence

on these numbers will be low. But that‘s still how they are thinking—and should

be thinking about it.

What they need to do is

formalize the process: Understand that this is a numbers game in which we need

to learn as fast as possible where we are on R, the impact of every measure on

reducing R, and their social and economic costs.

Only then will they be able

to make a rational decision on what measures they should take.

Conclusion: Buy Us Time

The coronavirus is still

spreading nearly everywhere. 152 countries have cases. We are against the

clock. But we don’t need to be: there’s a clear way we can be thinking about

this.

Some countries, especially

those that haven’t been hit heavily yet by the coronavirus, might be wondering:

Is this going to happen to me? The answer is: It probably already has. You just

haven’t noticed. When it really hits, your healthcare system will be in even

worse shape than in wealthy countries where the healthcare systems are strong.

Better safe than sorry, you should consider taking action now.

For the countries where the

coronavirus is already here, the options are clear.

On one side, countries can

go the mitigation route: create a massive epidemic, overwhelm the healthcare

system, drive the death of millions of people, and release new mutations of

this virus in the wild.

On the other, countries

can fight. They can lock down for a few weeks to buy us time,

create an educated action plan, and control this virus until we have a vaccine.

Governments around the world

today, including some such as the US, the UK or Switzerland have so far chosen

the mitigation path.

That means they’re giving up

without a fight. They see other countries having successfully fought this, but

they say: “We can’t do that!”

What if Churchill had said

the same thing? “Nazis are already everywhere in Europe. We can’t fight

them. Let’s just give up.” This is what many governments around the world

are doing today. They’re not giving you a chance to fight this. You have to

demand it.

Share the Word

Unfortunately, millions of

lives are still at stake. Share this article—or any similar one—if you think it

can change people’s opinion. Leaders need to understand this to avert a

catastrophe. The moment to act is now.

If you agree with this

article and want the US Government to take action, please sign the White House

petition to implement a Hammer-and-Dance Suppression strategy.

If you are an expert in the field and want to

criticize or endorse the article or some of its parts, feel free to leave a

private note here or contextually and I will respond or address.

If you want to translate this article, do it on a Medium

post and leave me a private note here with your link. Here are the translations

currently available:

Spanish

(verified by author, full translation inc. charts)(alt. vs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

French (translated by an epidemiologist)

Chinese Traditional (full

translation including charts, alternative

translation)

Chinese

Simplified

German

Portuguese (alternative

version)

Russian

Italian

(with graphs translated)(Alternative

1, Alternative

version on Facebook)

Japanese

Vietnamese

Turkish

Polish

Icelandic (alternative

translation)

Greek

Bahasa

Indonesia

Bahasa

Malaysia

Farsi (alternative version outside of

Medium)

Czech (alternative

translation)

Dutch

Norwegian

Hebrew

Ukrainian (alternative

version)

Swedish

Romanian (alternative

version)

Bulgarian

Catalonian

Slovak

Filipino

Hungarian (Alternative, with part 1, part 2)

This article has been the

result of a herculean effort by a group of normal citizens working around the

clock to find all the relevant research available to structure it into one

piece, in case it can help others process all the information that is out there

about the coronavirus.

Special thanks to Dr. Carl

Juneau (epidemiologist and translator of the French version), Dr. Brandon

Fainstad, Pierre Djian, Jorge Peñalva, John Hsu, Genevieve Gee, Elena Baillie,

Chris Martinez, Yasemin Denari, Christine Gibson, Matt Bell, Dan Walsh, Jessica

Thompson, Karim Ravji, Annie Hazlehurst, and Aishwarya Khanduja. This has been

a team effort.

Thank you also to Berin

Szoka, Shishir Mehrotra, QVentus, Illumina, Josephine Gavignet, Mike Kidd, and

Nils Barth for your advice. Thank you to my company, Course Hero, for giving me the time and freedom to focus on this.

Stay on top of the pandemic

Thanks to Tito

Hubert, Genevieve Gee, Pierre Djian, Jorge Peñalva,

and Matt Bell.

WRITTEN BY

Follow

2 MSc in Engineering.

Stanford MBA. Ex-Consultant. Creator of viral applications with >20M users. Currently

leading a billion-dollar business @ Course Hero

/https://www.niagarafallsreview.ca/content/dam/thestar/news/canada/2021/09/25/huawei-executive-meng-wanzhou-receives-warm-welcome-upon-return-to-china/_1_meng_wanzhou_2.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.